Running From Racist Crazy

On Being the Fortunate Grandchild of a Sicilian Yellow Dog Democrat

As a single parent, my Baby Boomer mom rebelled against her upbringing in the pre-Civil Rights Act South. She shared narratives, morals, and art wildly different from what she’d experienced as the youngest daughter of my grandmother, who I called Gammie. But because my mother enlisted Gammie to co-raise me, drama would ensue. Throughout my childhood, I routinely sat ringside for some educational arguments between two opinionated women from different eras.

“You should cut his hair.”

“Your president is a war criminal.”

“I can’t believe you walk around in those dungarees.”

“I can’t believe y’all watch Lawrence Welk.”

Born Genevieve Camp in 1907, Gammie was raised racist in the Jim Crow South, carefully taught white supremacy and Protestantism. Nevertheless, she married Salvatore (Sam) Francis Lucchese (pronounced Loo-KAY-see), a Sicilian-American writer, the son of immigrant boot-makers. A Catholic. Gammie’s unhinged Southern Baptist parents were very displeased with this union. They would not attend the wedding.

I’ve been wondering about that marriage, which would last six decades. With Sam Lucchese, did my grandmother intentionally, if subconsciously, pivot away from racist crazy? She knew she could not change with the times, and she knew fear ran in her blood. Perhaps if she married, say, a sane Sicilian, a man more liberal and level-headed than she ever would be, her descendants would fare better than her troubled forebears, who chafed at progress.

Spoiler alert: they have. Each subsequent generation (now three) in this branch of my family has been ever more kind, both to themselves, and to others, glad to be citizens of a diverse world.

(I’m sure my grandparents also loved one other. That always helps.)

After divorcing my father when I was an infant, my mom reclaimed her birth name: Mary Cecelia Lucchese. Her father’s name. (My brother and I kept Warren.) While she chased dreams in the 70s, I was often at my grandparents’, mostly under Gammie’s watch. It didn’t take long to clock the differences between the graying Southern belle and her raven-haired, spitfire daughter. My grandmother was not a violent woman, but when I told her, “My mom says she’s a hippie,” Gammie gasped.

“I never hit my girls!” she hollered. “But if she says that in my house I’ll put her over my knee and whup her with a hairbrush!”

Frightening, but also compelling. (Also, an empty threat.) This word hippie had power. Evoked fear. My fascination with language sparked, a fascination I would learn was more Lucchese than anything. And needless to say, Gammie’s protest was not nearly enough to stop me from being a hippie kid, grubby, long-haired, perpetually barefoot. All aspects my grandmother vociferously protested in vain.

No amount of criticism could cast a pall over the mushrooming multiculturalism of early 70s Atlanta. My brother, single mother, and I were part of it, one of the luckiest happenstances of my life. The bona fide Chocolate City / Wakanda that is modern-day ATL was just flowering, as unstoppable and natural-seeming as a change of season. My brother and I attended public schools, had black and brown friends, and enjoyed fabulous, diverse radio. (Shout out WQXI!) When our Andrew Young campaign signs were repeatedly vandalized, Mom was unfazed. One of my earliest memories is her jamming another blue-lettered sign into the dirt of our front yard, looking very much like a member of the Italian resistance. Very Lucchese.

When Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into law the year before my birth, he famously said of the Democratic Party, “We have lost the South.” Indeed, Gammie would defect to the Republicans. Sam Lucchese, however, would remain a “yellow dog Democrat” until his 1986 death.

Gammie looms large in memories and stories, but increasingly, my mind turns to Sam Lucchese. Despite my grandparents’ differences, I recall no arguments between them. I wish I’d asked more questions, but I was just a clueless kid enjoying fried chicken on a TV tray while watching The Flip Wilson Show.

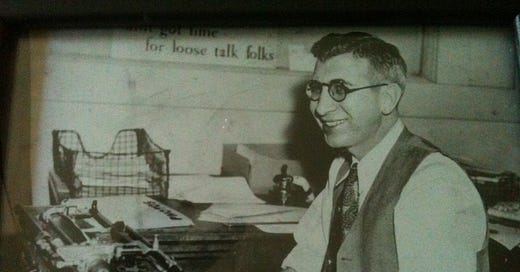

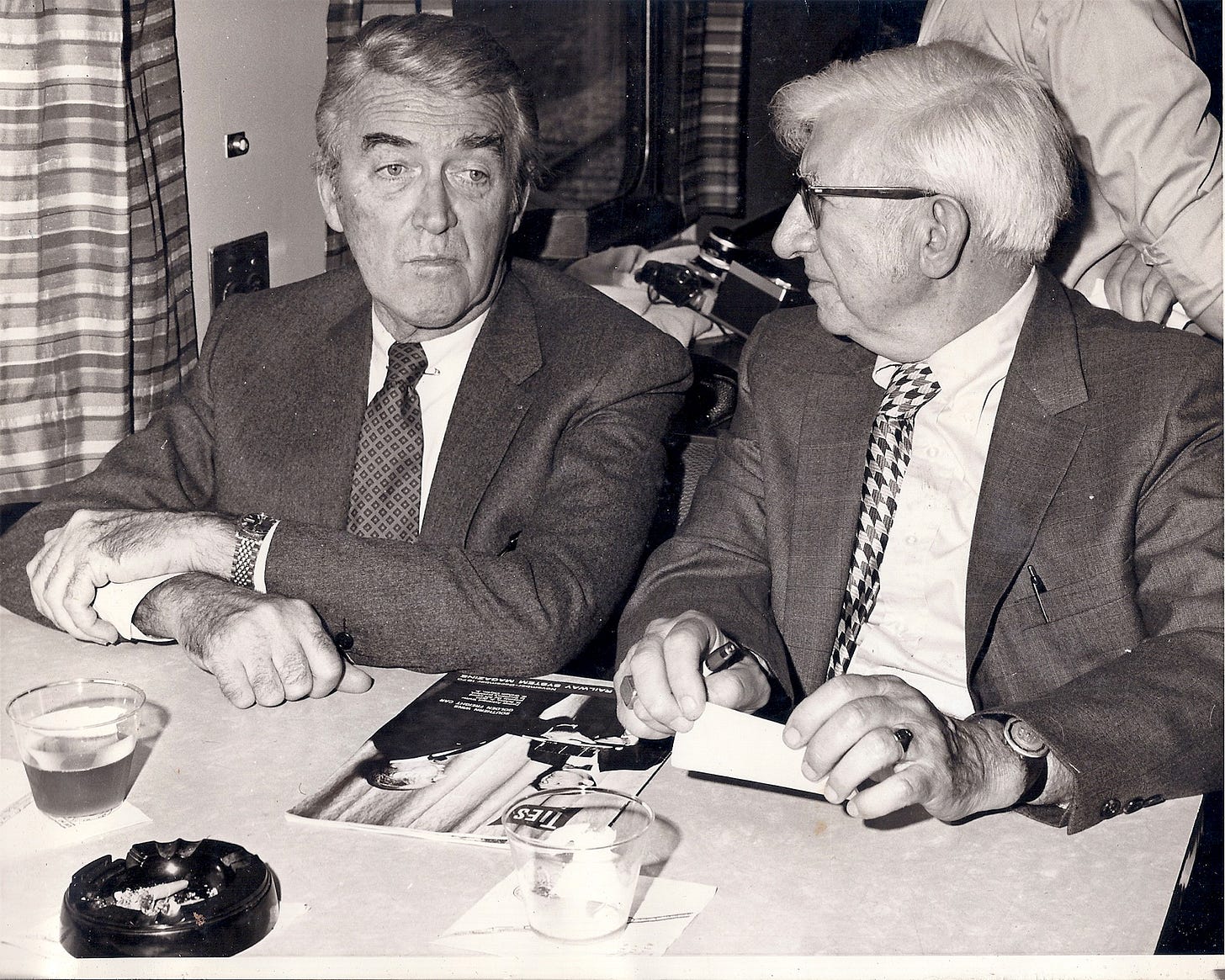

Sam Lucchese, who Gammie called “Casey,” did not fit the Sicilian stereotype. He was not outwardly passionate, was not a foodie, not a drinker, spoke no Italian. Coppola would not have cast him in The Godfather. Like his immigrant parents, Sam was a worker. He and my grandmother loved the arts, and Sam spent much of his life as the entertainment editor of several newspapers, including the venerable Atlanta Journal-Constitution. This work put food on the table and shoes on his daughters’ feet, and paid their tuition to Catholic school.

He was also the publicist for a little movie called Gone With the Wind. He and Gammie attended the December 13th, 1939 premiere at Loew’s Grand Theater, a stone’s throw from their home. They never got over it.

I recall my grandfather in his recliner, smiling enigmatically as his wife railed against protest marches, the Watergate witchhunt, Jimmy Carter’s popularity, et al. I see us watching All In the Family, the two of them laughing, sometimes together, sometimes individually at Archie Bunker’s bigotry, his willful ignorance, and/or Meathead’s righteous intensity.

Although I enjoyed no substantive conversations with Sam Lucchese, he is the ancestor I have become most like – in my work and politics at least. Perhaps also in my patience with febrile folk. The more I write, the more Lucchese I feel. (I once considered “Lou Casey” as a pen name.) The guy spent countless hours pecking away on a manual typewriter in the basement, churning out copy on deadline. I recall the comforting rhythm of the Underwood keys whacking the platen, the bing of the bell, the scraping of the carriage return. This was no chore for my grandfather. Today, the family members who spend hours doing that – albeit on computers, of course – are me, my cousin, Maggie, my wife, and my son (though none of us in the basement). Like my grandfather, I also enjoy editing, a skill I only recently discovered I possess.

I did not totally outrun the crazy of my grandmother’s people – the Camps – but it has been leavened by Lucchese genes, and by epigenetic choices, and maybe some luck. Most of that Camp crazy – schizophrenia, addiction, depression, mania – was unknown to me in childhood. My ignorance was no accident.

Gammie talked a lot, but rarely about her upbringing. Only after her 2000 passing at age ninety-three did I learn details of her mentally ill, racist, alcoholic father Josephus Camp. Her two siblings were also mentally ill, her brother institutionalized most of his life.

I recently finally encountered Josephus’s shrill, weirdly familiar voice via a file of letters, carbons, clippings, and even poems. Scary shit. Josephus’s chief obsession: desegregation, which he could not abide. He was also disgusted by women wearing pants. For decades, Gammie kept this file in an oaken rolltop desk, to be discovered after she was gone. Through circuitous means, twenty-five years after her death, it ended up on my porch a few weeks ago.

It had never struck me as odd that my grandmother displayed no photos of her father in her home. Dozens, however, of her grandkids and her daughters, and many high quality prints of celebrities she and Sam Lucchese had met on his press junkets: Natalie Wood, Cicely Tyson, Lucille Ball, Jimmy Stewart.

Interestingly, Josephus was a writer and editor, like his son-in-law, Sam. Like me. He was also an attorney, purportedly the youngest man ever to pass the bar in Georgia. Yet he never practiced law. Judging from the Josephus File, however, his main occupation, at least late in life, was as a clerk for the Georgia Highway Department. In carbons of letters, he repeatedly asks for a raise. His return address frequently changes. He is perpetually, operatically aggrieved.

At some point in 1951, when Gammie had long distanced herself from the Camps by building a life with Sam Lucchese, Josephus blew his brains out. My mother recently shared a memory of Gammie driving her to school that day, banging on the steering wheel, repeatedly saying, “I’m not gonna cry, I’m not gonna cry.”

In addition to the evidence in the Josephus File, my great-grandmother “Nanny” left behind diaries alluding to Josephus’ weeks-long drunks, his endless unhappiness. After Josephus’s suicide, Nanny called Gammie and told her to come clean up the mess. Gammie brought pieces of her father’s skull and brain home in a paper bag and buried it all in the backyard where, twenty years later, I would play.

To reiterate: I knew none of this growing up. Piecing it together in Gammie’s absence, I have come to believe one of the reasons she chose Sam Lucchese as her husband (she was beautiful, and had options) was his solid, sober nature. His Sicilian family had their eccentricities, but they weren’t racist lunatics. And they adored their daughter-in-law, who would enthusiastically convert to the drama and pageantry of Catholicism.

Sam Lucchese offered Gammie a different kind of life. I wish I could thank my grandmother for breaking the cycle, for not marrying an alcoholic, as many children of alcoholics do. I wish I could thank my grandfather for giving his beloved the opportunity to pivot.

I don’t begrudge being sheltered from the Josephus stories. I understand the impulse to protect, to shield from shame. I imagine Gammie’s pain, and my heart breaks across time and distance for my grandmother.

As horrible as it is, however, I’m glad she didn’t burn the Josephus File. She easily could have, but she didn’t. Perhaps she wanted us to realize how far we’d come, and what she’d rejected to make a family with a man so unlike her father. Perhaps.

So. What to do with all I finally know?

This. Words, churned out over hours, like Sam Lucchese would have done.

With his wife’s crazy family banished to the edges of their life, Sam Lucchese writes, and writes, and writes. He fills the dank basement with percussive typing, words from his mind, to his hands, to the page. Words to build a life in a changing world. The woman who allowed him to save her is upstairs, mothering. Their home rings with music.

Decades down the line, mine does, too. I am grateful.

lou, ha ha, we share a Beetle past!! the one we had when i was a kid was blue with a rag-top. keep them typing sounds a'comin'. xxxcm

Great read. Where in Sicily do the Luccheses hail from? Do you know?