MIDWIFE: IVAN “IVY” VAUGHAN

MIDWIFERY CREDENTIALS: THE BEATLES

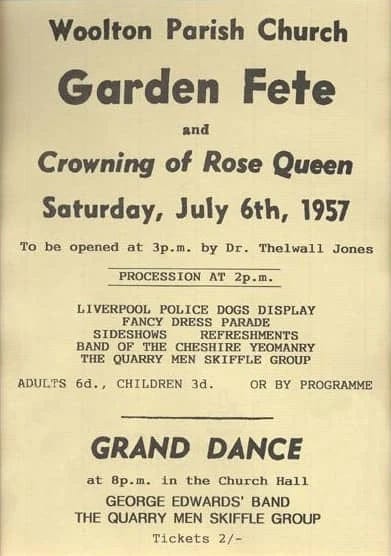

It’s painful to contemplate, but in an alternate universe, fifteen-year-old Paul McCartney did not attend the Woolton Parish Church Garden Fete (intriguingly pronounced by Brits as “FATE”) on Saturday, July 6th, 1957. Perhaps in this counterlife, he was beset by grief over his mother’s death from cancer nine months prior, and he chose to stay in and listen to his few 45s, playing guitar or piano in the modest home he shared with his jazz musician dad and his little brother, Michael.

But in our universe, Paul accepted an invitation to the fete from his mate, Ivan “Ivy” Vaughan. Ivan reckoned Paul would enjoy the Quarrymen, a skiffle group led by his troubled sixteen-year-old acquaintance, John Lennon. Astonishingly, documentation of what Paul witnessed exists. (Also, amazingly, a photo, see below.) On the scratchy recording, you can clearly discern Lennon’s distinctive, soon-to-be iconic howl over quite a racket, a howl he would hone for the rest of his too-short life. As a producer once noted to me, “Lennon sang very loud, like in the red. In the pre-fame days, that was the only way he could be heard, and up ‘til about ‘65, even on early Beatles ballads, he is essentially shouting.”

Of all the Quarrymen gigs, one can’t help but wonder why the Church Garden Fete was the only one recorded. The only Quarrymen gig at which the history of popular music would significantly change is the only one we can still hear. Makes ya think.

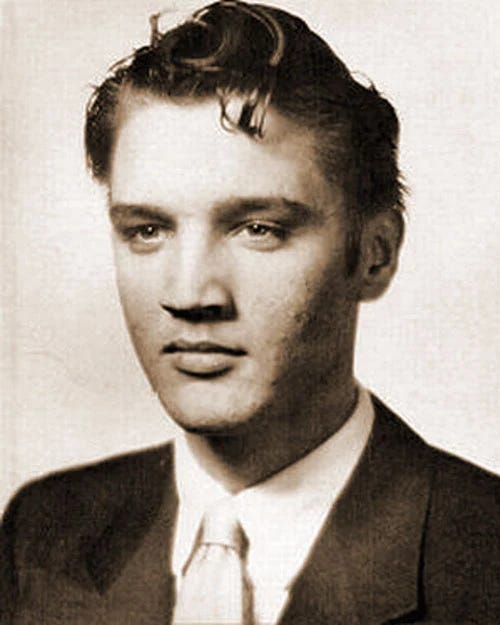

In addition to skiffle tunes by Glaswegian phenom-of-the-day Lonnie Donegan, the Quarrymen’s repertoire featured cover versions of up-and-comer Elvis Presley, whose work had only reached Liverpool the previous year. Both Lennon and McCartney would retain vivid memories of hearing “Heartbreak Hotel” on the radio in 1956, and learning it by ear.

Paul was impressed with the Quarrymen’s cocky frontman, even as he realized John hadn’t tuned his guitar properly, and made up words to some songs. During the band’s break, Paul introduced himself, played a little piano for the group, and audaciously asked if he could “have a go” on John’s cheap guitar. He tuned it, flipped it ‘round so he, Paul, a lefty, could play it upside down, and executed a note-perfect version of Eddie Cochran’s recently-released “Twenty Flight Rock.” It’s worth noting the song is very wordy, and Paul knew all the words and was eager to show Lennon this particular skill. John was duly knocked out (though he wouldn’t let on ‘til later), liked that this kid looked a little like Elvis, figured he would attract more birds, and maybe felt the hand of fate touching his shoulder. He soon invited Paul to join the Quarrymen. Within weeks, they were writing songs together, eye-to-eye.

So thanks, Ivy, for inviting your mate Paul to the fete that day.

More about Ivy, a fascinating character, HERE.

Lastly, for the tape, we can thank retired Liverpool policeman Bob Molyneux and his portable Grundig TK8 tape machine. (He was 15 in the summer of ‘57.) We can also thank him for wisely storing the fragile reel in a vault until 1994, when EMI would purchase it, and the Grundig, from Sotheby’s for 78,000 pounds (about $100,000, which seems a steal).

MIDWIFE: MARION KEISKER

MIDWIFERY CREDENTIALS: ELVIS PRESLEY

First and foremost, although she is most renowned for being the first to record an 18-year-old electrician’s apprentice and truck driver named Elvis Aaron Presley, and then to repeatedly alert her bullheaded genius boss, Sam Phillips, that the kid was worth his time, Rhodes College graduate Marion Keisker’s list of achievements is long. She was not Phillips’ “secretary” or “receptionist.” Among other things, Keisker, a local radio celebrity, was crucial to building and running Phillips’ dual Memphis businesses,: The Memphis Recording Service and Sun Records, both housed at 706 Union Avenue.

The Memphis Recording Service (“We Record Anything, Anytime, Anywhere”) recorded weddings, choirs, conventions, sermons, even funerals, and, for a fee, allowed anyone to come to 706 Union Avenue, get recorded, and walk home with an acetate disc of their work. Both Keisker and Phillips operated the recording equipment and the lathe – which pressed the taped sound onto disc.

Phillips and Keisker created the Sun Records label for the rising market of blues and R & B music – genres Phillips unabashedly loved. Elvis also loved that music, but equally loved pop and Country & Western, and could, and would, sing all of it. (The term “Rock N’ Roll” would not be in the mainstream lexicon for several years.) By the time Elvis darkened the door of 706 Union Avenue on Saturday, July 18th, 1953, Phillips – with Keisker’s aid – had recorded soon-to-be legends Howlin’ Wolf, B.B. King, and Rufus Thomas, but was still struggling both financially and psychologically, seeking electroshock therapy for depression brought on by fear of failure. According to Keisker, he repeatedly said, “If I could find a white man who had the Negro sound, and the Negro feel, I would make a billion dollars.”

Although he would not make nearly a billion dollars, when the answer to that prayer walked in the door, Keisker recognized it before Phillips did. Phillips needed to be persuaded, and Keisker would be the persuader. Although Elvis himself reportedly only publicly acknowledged her once as the reason he got his shot, all biographers agree on this point.

Phillips was absent on that sweltering day when pimply, greasy, magnetic Elvis availed himself of the Memphis Recording Service to record two pop ballads for $3.25 (about $40 today), allegedly for his mom, Gladys – “My Happiness” and “That’s When Your Heartaches Begin.” As per usual, Phillips had left Keisker in charge. Before placing Elvis and his cheap Kay acoustic guitar before a microphone, setting levels, and hitting RECORD on the tape machine, Keisker asked the shy kid what kind of music he sang. “All kinds,” he said. She asked who he sounded like. Although he idolized Dean Martin, he answered: “I don’t sound like nobody.”

When Elvis bounded out the door with his acetate, Keisker noted his name, and added this commentary: “Good ballad singer. Hold.” She pushed Phillips to call Elvis back. Phillips did, and they recorded two more ballads – "I'll Never Stand In Your Way" and "It Wouldn't Be the Same Without You" – but Phillips was unimpressed. At Keisker’s urging, he gave Elvis yet another chance, setting him up with locals Scotty Moore on guitar and Bill Black on doghouse bass.

The ensuing recording session is in the history books as one that began unpromisingly but, after hours of failure, yielded, in the dead of night, a wildly compelling version of blues artist Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup’s “That’s All Right,” which Phillips immediately, and rightfully, recognized as gold.

To this day, that one minute-fifty-five-second recording sounds like nothing else.

One hopes Keisker was gifted with good sleep that night, because her largely unheralded actions had made not one, but two men’s dreams come true.

Thanks, Marion Keisker, for trusting your ears and instinct, and for honoring that impulse to repeatedly bug your stubborn workaholic boss that his ship had come in. You changed the world.

Addendum: Keisker left Sun in 1957 and joined the Air Force, where she led a distinguished career until retiring as a major in 1969. But she was not done. The 70s and 80s saw her become both a renowned performer in Memphis theater, and a significant force in the Women’s Movement. Read more about her HERE.

I've always loved Marion's story. Guralnick's Sam Phillips bio (and of course, his two Elvis volumes) are essential. Thanks for spreading the news - her name isn't mentioned nearly enough in rock'n'roll, or the history of pop culture in general.

call the midwife.