“People forget years and remember moments. Seconds and symbols are left to sum things up: the black shroud over the pool. Love, in its shortest form becomes a word.”

Ann Beattie

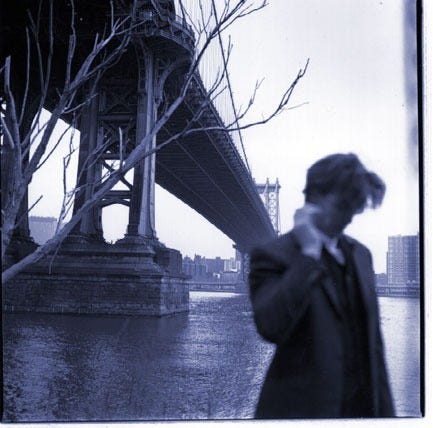

In the late afternoon of Friday, February 1st, 1985, I pulled my belongings from a sedan parked outside 208 West 23rd Street, NYC, and piled them onto the sidewalk. I was nineteen years old, sleep-starved, and about to face the consequences of one of the rashest decisions of my life.

The car was my neighbor Paula’s. She and I had just pulled in from Athens, Georgia, where I’d spent most of 1984 playing bass, working at Kinko’s, and enjoying my first taste of low-overhead independence. Upon learning of my half-baked plan to relocate to the Big Apple, Paula, bound for Montreal, had offered me a lift up the Eastern Seaboard. Leaving Georgia at dusk, we’d driven straight through. Over twenty or so hours, we’d shared wheel-duties, fending off fatigue with conversation and coffee (and youth). Attempting to nap in the backseat somewhere along the way, we’d become much better acquainted, skin-to-skin, during which Paula said, “So you do like girls.” After parting in NYC, I would never see her again.

Why do some memories retain clarity while others fade, or vanish altogether? Because adrenaline, I think. This hormone, both friend and foe, operates like amber, encasing, even enshrining, certain episodes.

In my late teens and early twenties, I threw myself into adrenaline-producing situations on the regular. Some recklessness turned out to be charmed. Partly due to dumb luck, and partly due to kind strangers, my regrets and scars from those years are few.

40 years on, I’m still a New Yorker, albeit a Catskillian rather than a Manhattanite. Nevertheless, those fraught first NYC months come to me easier than recollections of what happened last week in Phoenicia, my home of twenty-two years.

As Tobias Wolf said, “Memory has its own story to tell.”

In the deepening gray of that February ‘85 afternoon, a light, icy rain fell on me and my baggage: acoustic guitar, two basses, practice amp, and a foot locker packed with thrift store clothes, paperbacks, and cassettes.

Huddled in damp, vintage tweed, I faced down a bone-chilling breeze from the nearby Hudson River. A secret pocket held about $500 from selling Christmas trees in an Atlanta parking lot. I had no credit cards, bank account, or job prospects; no band or girlfriend for the first time since I was fourteen. No debts.

My goals? Find a band, find a stage. Perform. Figure out how to harness NYC’s unique energy, invest my work with it; make a living, or maybe “stupid money,” doing so. I’d done a lot of rocking by age nineteen, and I was good at it, but while I’d co-created some exciting spectacles and some decent music, I sensed my life’s work would evolve amid this severe, potentially rewarding terrain. Here, the boldest of artists, wealthy or not, lived well, walking streets rich with languages and food and music and insights from every corner of the globe.

Nestled in my wallet was the phone number of impresario and activist Jim Fouratt. We’d hit it off when I first adventured in NYC as a teenaged bass player with Wee Wee Pole featuring RuPaul in ‘83, and Athens combo Go Van Go in ‘84. I didn’t know it then, but Jim’s digits would be akin to winning lottery numbers. I initially hoped he’d just help me find a band, which he would do, but his connections to a network of benevolent artists would also save me from imminent crisis, and root me to the Manhattan bedrock until 2002.

I’d fallen hard for the Big City on those ‘83 and ‘84 tours. In that clarifying love, I’d accepted an invitation to leave behind everything I knew and cohabitate in a one-bedroom Chelsea apartment with a troubled couple, fellow Atlanta expats. I had no other options. Unwise it may have been, but it was not a mistake.

I buzzed apartment 206, alerting my soon-to-be roomies of my arrival. I’ll call the roomies Melody and Harry. Harry was Melody’s and my erstwhile high school acting teacher, a kind of mentor to fatherless me, and other latchkey kids with absent or dead dads. Once Melody turned sixteen, when she and I were juniors, she’d become Harry’s lover, a clandestine relationship I was entrusted not to reveal, which made me feel important, anointed.

In 1985, Harry was twenty-nine, an aspiring playwright. When talented, beautiful Melody enrolled in Juilliard, he quit teaching, pulled up stakes in Atlanta, and followed her. She soon dropped out, disenchanted with performing, and took an office job. Harry had found bartending work. While doing no playwriting, he was pointedly not encouraging his girlfriend to keep acting. This was the unhappy situation they’d invited me to join.

To make matters more complicated, Melody and I were more than friends. When I’d been in NYC with Wee Wee Pole, she and I had enjoyed a secret “lost weekend” together. Before Go Van Go’s Peppermint Lounge gig, we’d canoodled pretty intensely on the tarry, 18-story rooftop of 208 West 23rd while Harry was in the apartment watching TV and smoking. Periodically surrendering to our intense mutual attraction, I now believe, wasn’t just pleasure, it also chipped away at Harry’s hold on us, his formidable, uncharitable will. Parts of us knew we needed to sever him from our lives, but we were too immature and insecure to fully trust those impulses.

Prior to my arrival to live with them, via furtive letters, Melody and I had pledged to return to what is now called “the friend zone.”

As Harry and Melody helped me drag my things out of the wet February chill and into the overheated foyer of 208 West 23rd, I thought about that pledge, my heart pounding like a kick drum.

Once all three of us were in the tiny apartment, with my belongings crammed into the corner where my roomies had previously lounged, I realized this arrangement was going to be awkward at best. I’m sure Harry and Melody did, too. Did they think having me aboard their sinking ship would distract from the inevitable? Like getting a pet? Or was the invitation a way of speeding things along? It was bonkers.

Of the handful of memories I retain of those couple of months, most are tense, with forced camaraderie, stony silences, walking in on Harry supine in the bathtub, flushing the toilet for him, trying not to ogle Melody in her pajamas, burrowing beneath a rank pillow for privacy, and sadly cooking my daily Wheatena in the kitchenette.

Going forward, I would scribble letters home in the stairwell, the distinctive scent of NYC garbage wafting up. Had I made a mistake? Because this was definitely starting to feel like a mistake.

I registered with a temp agency. A manager with sweet, pitying eyes sent me to various businesses where, in down-at-the-heels Weejuns, ill-fitting thrift-store duds, and an awful haircut, I executed mindless clerical work for minimum wage. My daily lunch was either a pizza slice or a street hotdog. I often ate dinner solo at a blessedly cheap Chinese restaurant, or a falafel joint. Several times I caught my reflection in a window and did not recognize that depressed scarecrow.

I think my bedraggled state helped Melody keep her distance. Except for that night she came back from carousing. Brimming with drunken brio, she straddled me on the futon as Harry slept in the bedroom. After returning a few woozy kisses, I pushed her away. In a heated whisper, I chided her craziness as she stumbled back to their bed, giggling.

Perhaps not coincidentally, Harry soon informed me I needed to leave, and soon. Melody didn’t argue. Of course there’s no way Harry didn’t know what was going on, and what had gone on, between his girlfriend and me. He was no intellectual dummy, but, like Melody and me, he was scared to acknowledge the emotional truth of the situation. No brave adult was forcing the issue, calling it as it actually was.

Thankfully, my first New York City springtime was coming on. My will to stay had wavered in those frigid, lonesome, late winter days, but the lengthening russet light over the avenues, the warmth on my sleeveless arms, and the blossoms bursting in the parks all contributed to my resolve to remain. I couldn’t shake the feeling that my future was awaiting me where I was, if only I hung on a little longer.

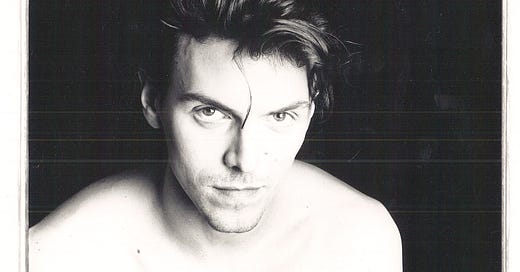

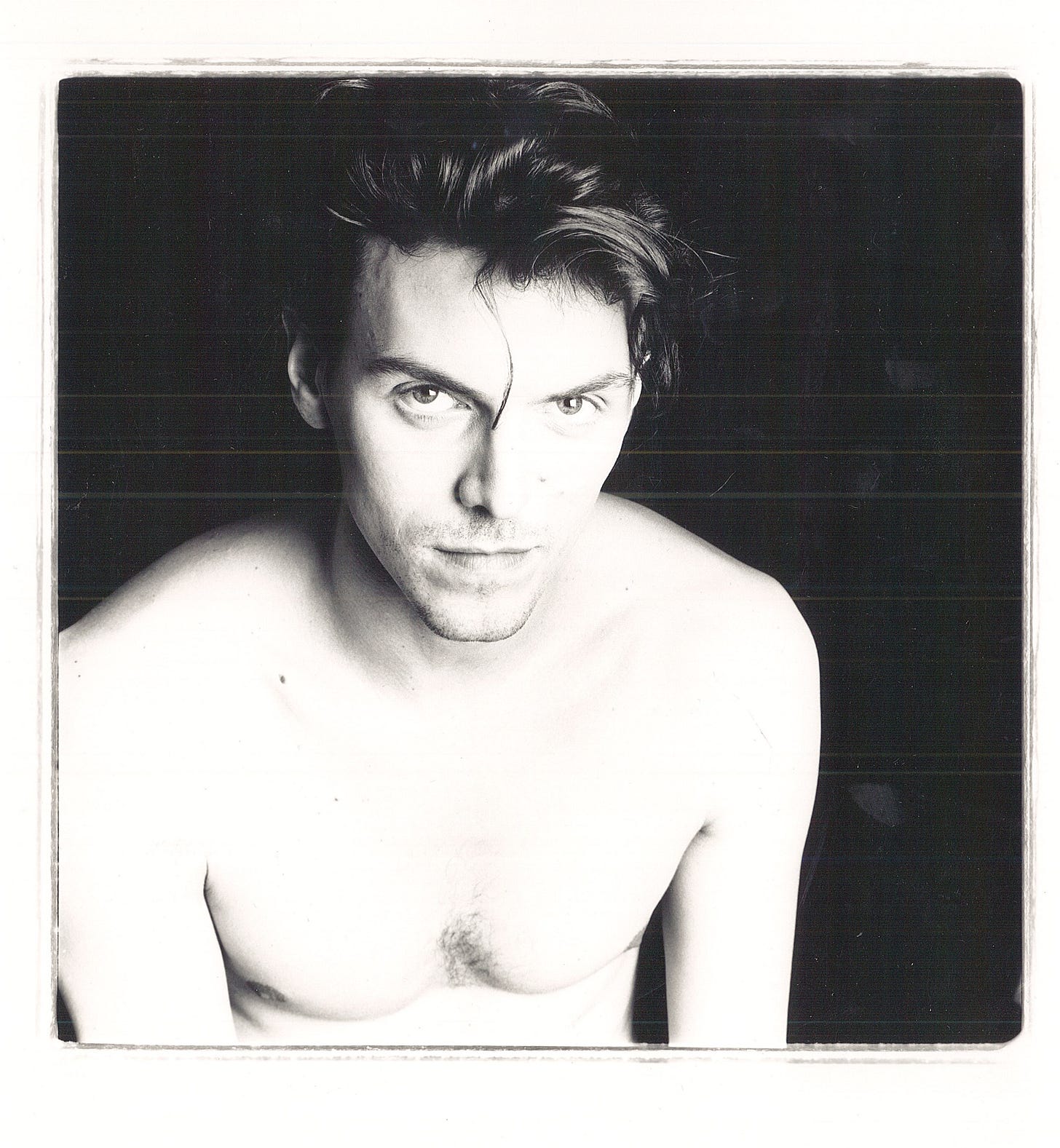

In the nick of time, my life pivoted. Sometime around my 20th birthday – March 29th – Jim Fouratt put me in touch with Mark Abramson and Keiko Bonk, guitarist and lead singer, respectively, of His Master’s Voice, an arty rock band with management, and an LP out. They needed a bass player. Their fantastic drummer, Jay Dee Daugherty had played (and still plays) with Patti Smith. Not only did I get the gig, I got a life.

It so happened Mark and Keiko’s friend Vinnie Signorelli was touring Europe and needed someone to sublet his two-bedroom railroad apartment in Ridgewood, Queens. The rent was $300 a month. I jumped at that. Once free of Harry and Melody’s crumbling world, the kindness of more artist strangers enabled me to thrive. (My story with Harry and Melody was not over.)

Mark and Keiko also introduced me to Maggie and Doug, proprietors of King Tut’s Wah Wah Hut, a bar at the corner of Avenue A and East 7th Street. King Tut’s needed a dependable non-junkie (that’s me!) to wash glasses on weekends. I would soon be promoted to bartender and manager, heading home in the wee hours with wads of tax-free cash in my biker jacket pocket. Incredibly, I was never mugged.

Mark and Keiko, true artist-hustlers, possessed two leases, one for a Chelsea loft, one for a tenement on Avenue B between 11th and 12th. By autumn of 1985, they’d set their new bassist up in the latter. As the leaves turned, I was making plans to travel with His Master’s Voice to Los Angeles, and to Mark and Keiko’s home state of Hawaii, where we would unleash our intense music on unsuspecting, sun-kissed audiences.

By winter, I was a New York musician with an apartment, income, and friends, living well and on the cheap when that was still possible in the City That Never Sleeps. My life was a good balance of stable, yet never boring. I actually slept well, and often.

Every February since that momentous year – of which I’ve documented only a fraction here – my mind replays memories of those chaotic, adrenalized times. With awe, I consider “sliding doors” moments. My approaching 60th birthday feels significant, so I’ve plumbed a bit deeper on this 40th anniversary of leaving the South to find my life. As usual, documenting certain details reveals others I’d not thought about in many moons. Especially considering the state of the world at present, these forays have been particularly therapeutic. Mine was not a misspent youth.

Thanks for accompanying me, dear reader. If you’d care to share any acts of recklessness and/or kindness that changed your life for the better, please do so in the comments.

Sitting in the bay window of the 1910 Victorian in which I co-raised a beautiful human, I am grateful for all of 1985, even the unpleasantness of the 23rd Street living situation. All led to this moment, which is pretty good. Although things got even more dramatic with me and that doomed couple, I likely would not have ended up in my beloved NYC without Harry and Melody, and thus not here. Gratitude can be complicated.

My mind is still pretty sharp, and my heart, a cardiologist recently informed me, is “gorgeous” and “perfect.” But I’m having trouble retaining new names. Those of this story’s heroes, however, are forever seared within me: Jim, Mark, Keiko, Maggie, Doug, and Paula. May their kindness, and their names, always be so easily retrievable.

I LOVE this! It's beautifully and evocatively written. I also extremely recklessly threw myself into NYC in 1998. I had $800 and my former college roommate was in the musical Cats and holding a bedroom for me in his apt on 102nd and Amsterdam. An introvert in a tiny apartment full of Broadway actors and Broadway actor wannabes! It was intense. Sometimes I'd wake up and I couldn't walk for all the people strewn over the floor, each sleeping on one of the sofa cushions. I did find a job at Henry Holt as an editorial assistant but then my actor friend, it turned out, was not paying the rent and decamped for Chicago to play Harry Houdini in Ragtime. I had three days to get out. My mother said she'd send me a plane ticket back to Detroit but wouldn't give me a cent to stay in NYC so I squatted in an abandoned building on 109th and Amsterdam while I saved as much as I could from my $1600 a month salary. Eventually I found a room in the East Village, friends, lovers, short stories,etc etc. I do not regret a SECOND of that experience. It was absolute magic.

You're such a good writer, Robert. I have plenty of memories that would make good -- even exciting -- tales, but I fear I lack your prodigious skill. Having grown up in Southern California in the 60's my early life was packed with episodes of sex, drugs, rock & roll, smuggling adventures, even guns. Like you, I can't complain since it all brought me where I am today. New York has been a big part of the story as well. I love the quote “Memory has its own story to tell.” And I love everything you write.