Pride Month always returns me to the 80s-90s East Village, where I was lucky to spend a formative chapter of my life. In that pre-internet age, my peers and I enjoyed both busy-ness and magical boredom. Our algorithms were not yet assembled, not yet telling us who we were and what we should pay for, with money, or with our attention.

I fondly recall a radical inclusivity that cannot easily be reduced to a soundbite, or a phrase. Picture if you will: living and loving on a fluid spectrum without realizing it is a fluid spectrum, without even thinking of affixing labels to proclivities, desires, identity. Curiosity was the connecting thread among us, often ravenous curiosity. At the same time, mystery was more accepted, even embraced. In this funky, insular ecosystem, we cluelessly thrived.

While my orientation on that fluid spectrum could be described as tending towards what we now call “heteronormative” (too many words there), many who shepherded me through those important years would probably describe themselves as queer. Then they’d excuse themselves to go do something much more interesting, like create art, or help someone else do the same.

What remains in me is not labels, but undimmed memories of a tribe stepping up to show me resonant versions of family, faith, love, grace, and courage.

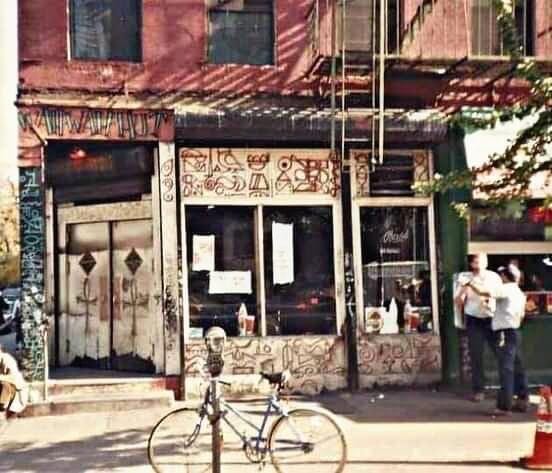

Crucial for me was King Tut’s Wah Wah Hut, an arty oasis on the corner of Avenue A and East 7th Street. Not long after I arrived from Atlanta, proprietors Maggie and Doug hired me first as a dishwasher, then bartender, then bar manager. It was 1985. I was twenty. Rather than work toward a BFA, I’d moved to Manhattan with $500, a bass, and a trunk full of thrift store clothes.

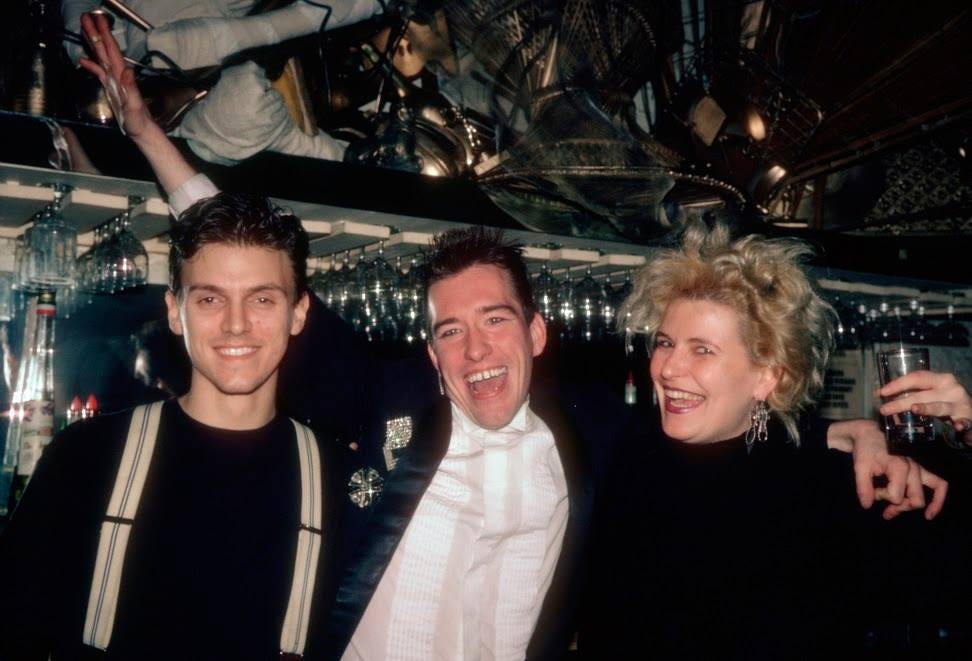

King Tut’s was more than a job. I’ve described it as a kind of pansexual punk rock Cheers. (If anyone wants to help flesh out this million dollar concept, I’m game.) That pitch doesn’t exactly cut it, of course, but it’ll do for now.

In the four years, on and off, that I was a King Tut’s Wah Wah Hut employee, my fellow service workers and I hung out, divvied up tax-free cash tips, turned each other on to music, turned each other on, played in bands, and performed for each other, both on stages and off. We could not have cared less who anyone was intimate with, or what he/she liked to wear, or if they chose to make out with a friend in the phone booth one woozy night, or experiment one lost weekend with something, or someone, strange. It was a time of possibility, of play.

Judgement free? Not exactly. Anyone who tried to shame us would be shunned. With style.

Impresario-activist Jim Fouratt started the ball rolling for me. As I wrote here, I’d met him while on tour with Wee Wee Pole featuring RuPaul. Jim connected me to a band that not only secured me an Ave. B tenement apartment, but also led directly to King Tut’s, which begat my first working gig with international garage rock titans the Fleshtones, which begat meeting my wife, Holly, and a life that now includes the 1910 Victorian in which I type this. Most importantly, it all led to Holly’s and my son, Jack.

In those first few years, pre-marriage, pre-fatherhood, I spent many hours burning up shoe leather on the streets of Alphabet City, often in the pre-dawn. I was never mugged. With the King Tut’s crew, I broke into the Pitt Street Pool to swim, and watched many a sunrise over Tompkins Square Park, the last Manhattan park with no curfew, where fires burned and kids a little less lucky than me camped. Until the riot of 1988, now regarded as a harbinger of gentrification.

Prior to East Village living, I did not know this word gentrification. I would learn. Unbeknownst to me, I was in the last wave of artists who could live cheap and well in NYC. My quality of life included good, inexpensive food, a reasonable amount of space, low overhead, and an abundance of art, beauty, and adventure. I’d arrived just in time.

Of course it wasn’t all fun. As the 80s played out, AIDS ravaged my community. It still chills me to recall friends dying in their prime. Seeing them on the streets, in Beth Israel, wasting away, anxious, angry. An important takeaway was the realization that, while living in fear of illness, our pride could, and would, intensify. Much doubling down on outsiderness ensued, even more flaunting, more celebrating. A grand fuck you to the government, to those who would wish us dead, to the specter of death itself. I’m recalling Wigstock ‘86, at which Lady Bunny recruited me to perform. In the Tompkins Square Park bandshell, I helped back up a cast of performers, drag and otherwise. At this life-changing gig, the Fleshtones first saw me do my thing. Two months later I was in the band. The following spring we were opening for James Brown, playing to about 6,000 people at Le Zenith arena in Paris.

As the AIDS epidemic surged, I was fortunate to witness the amazing ACT UP transform grief and anger into action, marching on government buildings in a state of sustained rage, shaming Burroughs-Wellcome into lowering the price of AZT by 35%. This was real, tough love, a kind of badassery I’d never seen. A lesson.

There was so much love. Some at King Tut’s wished for stardom, but at the same time, were loath to leave the love we knew in East Village obscurity. It was uncommon, this love, infused with, but sometimes beyond, sex. An amalgam of friendship, family, foxhole intimacy, erotic fascination, and besotted crushes, spiced with a healthy degree of disdain and pettiness, a little destructive behavior in the thick of the rampant creativity. Perhaps in the timeless parts of ourselves we knew how special it all was, how brief it would be. We could not articulate this, but even if we could, we would not have done so because it would’ve been very uncool.

I quit for good when King Tut’s Wah Wah Hut was sold in 1990. It limped along for a couple years under different ownership. 112 Avenue A would eventually become Niagra, which is still in operation. Like King Tut’s was, it is open ‘til 4 AM every night/morning.

As the new millennium approached, almost all my old friends and co-workers let go, or they fled, or they were priced out of the neighborhood, the life, by gentrification. Everyone, in their way, moved on, relinquishing apartments, turning the page on a chapter lived with gusto. More than a few died young, and we mourned them, and mourn them still.

My little family trio departed against our collective will on December 30th, 2001. We all cried. It got messy indeed. The hardest transition of my life thus far.

Jack, on the other hand, transitioned fine. Our son was just shy of four when we left the East Village for the Catskills. But evidently, even though their memories of that time are scant, it seems the old East Village did not totally leave Jack. They’re now a twenty-seven-year-old writer and filmmaker, brazen in their work and life, part of an inclusive community of their own. I see them. Jack gives me hope, makes me proud, takes me back. I daresay the life-altering kindness once bestowed on me is connected to my kid’s actions; the embrace of possibility, the defiance of limitations, all manifesting beautifully before my fortunate eyes. And not a moment too soon.

With the gift of time, I’ve learned both the power and the poverty of language. Sometimes a word is a perfect container for a concept, sometimes a word is just a signpost to a vast vista. In my personal lexicon, queer is one of the latter.

Decades on from my East Village era, I’m pretty robust, but my short term memory for some things is starting to go. Mostly, when I meet new people, unless they deeply irritate me, I can’t remember their names. It is vexing.

Part of my memory, however, is ironclad, at least for now. Seems I will never forget the names of the folk – queer and queer-adjacent – who took me in and/or steered me toward the better part of my life: Jim, Sally, Vinnie, Maggie, Doug, Tom, Jesse, Stacy, Kate, Richard, Byron, Byron, Luis, Itabora, Michael, Grace, Stan, Jo, Lucy, Annie, Dany, Ande, Paula, Denise, Monica, Effie, Ethyl, Wendy, Ida, Chuck, Curtis, Chris, Lady Bunny, Bob, Marleen, Baby, Pam, Deb, Mark, Keiko, Gerard, Bernard, Nick, Henry, Hattie, George.

All helped me become me, and showed me signposts to vistas and possibilities I didn’t know existed. For these people I have no single descriptor, but lots of love. And, in a word, pride.

I was watching from afar.

Amazed and yes, very proud

of you. Epic historical post.

Hi Robert, I read this upon publication... Brought back lots of similar memories of the same places. (I DJ'd at King Tut's after it changed ownership.) And some of the same people. (Jim Fouratt took me under his wing as well.) What I always loved about our music world, from the earliest days, was its Don't Ask Don't Tell mindset which, back when more formal areas of employment were actively prejudiced, seemed like radical inclusion. I came of age as a teen in London simply enjoying the fact that my music world had all sorts. In NYC, especially with personally gravitating into the club scene, that mindset was much more overt, more celebratory, and was an aspect of NYC I absolutely loved. Like you, fond memories of Wigstocks (and Mermaid Parades). And of the club kids who sadly went awry, less from disease (though I lost friends to AIDS) than drugs. Thanks for sharing your Pride.