Part 1 HERE

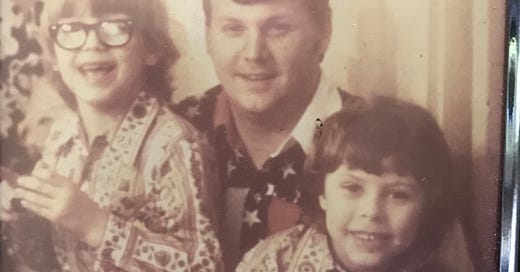

The last time I see my father is at my 7th birthday celebration. Spring, 1972. Another combo party for my older brother Britt and me. There he is, Robert Burke Warren, Sr., Burke to his friends and family, Daddy to me. It’s a spend-the-night party, but he won’t stay.

Daddy sits “Indian-style” on the living room rug with his acoustic guitar. In a cluster of boys, he effortlessly plays and sings “Home Grown Tomatoes,” “Puff, the Magic Dragon,” “Take Me Home, Country Roads,” “If I Had a Hammer.” I am proud of him. He is self-taught. Handsome. Just shy of thirty-one. An ex-Marine, a captain. I will learn he was dishonorably discharged, though no one can, or will, tell me why. Troubled, unemployed, magnetic. English Leather cologne, cocktail breath. Half my DNA from this human who will not grow old.

This will be my only memory of my divorced parents in the same room. My beautiful, dark-haired mother remains at the periphery, lit by a Carlton ember. She watches the person with whom she brought two unplanned sons into this realm. She will rarely discuss him after this night.

A couple weeks later, Burke’s cousin is passing through town and invites him to carouse at the Atlanta Hilton bar. After getting blind drunk, my father drives his Chevy Impala at high speed off I-85 and into an embankment. Mom tearfully tells us Daddy “fell asleep at the wheel” and the steering column crushed his chest. He “died instantly.” We are devastated, wracked by sobs. We do not attend the funeral, at which Daddy’s second wife throws herself on the closed coffin.

He’d wanted to drive her nicer car to the Hilton. She’d refused. They’d fought. She’d thrown his keys at him and yelled, “Go crash your own car!” Her last words to her husband.

A few years on, I’m on the cusp of adolescence, exploring the attic. I discover a police report in a box labeled BURKE. Included is a photo of my father’s crumpled Chevy, windshield spider-webbed. The report notes his blood alcohol level as very high. A sketch shows the trajectory of the Impala leaving the road, briefly airborne. So far does his car fly, it is not discovered until the following afternoon.

There are no photos of Burke displayed in the house where I grow tall like him. As hormones kick in, I am bequeathed his smart hands, and strong, long legs. A young woman will note I have “daddy shoulders,” thus immortalizing herself in my memory. My Mr. Magoo eyes, however, are courtesy my paternal grandfather. They rule out any athletics involving a ball, but not untold hours teaching myself bass and guitar by ear, listening to records repeatedly, just like my dad. Coke-bottle-thick glasses and wonky peepers will shape my life significantly.

In the years to come, I dream of my father. I’m standing behind a graying version of him on an escalator going down. I run to embrace him in my maternal grandmother’s living room. In these and other dreamtime episodes, I euphorically realize my father’s death was a big misunderstanding. Sometimes the revelation is celebratory, other times it’s a quiet joy.

Awakening back in my timeline involves brief re-grieving, an echo from someplace in my body untouched by time. Part of my mind, perhaps protective, willfully initiates forgetting, while another fitfully grasps the ebbing dream. The forgetting is usually successful. But not always.

The remembered dreams featuring my farewelled father are strangely crystalline, their reverberations perpetual.

Although Social Security survivor benefits help pay various bills, mentions of Burke in my childhood homes are few. After a falling-out between Granddaddy Warren and my mom, we become estranged from the Warren side of the family. Estrangement will be common among my kin.

Getting to know my father falls to me.

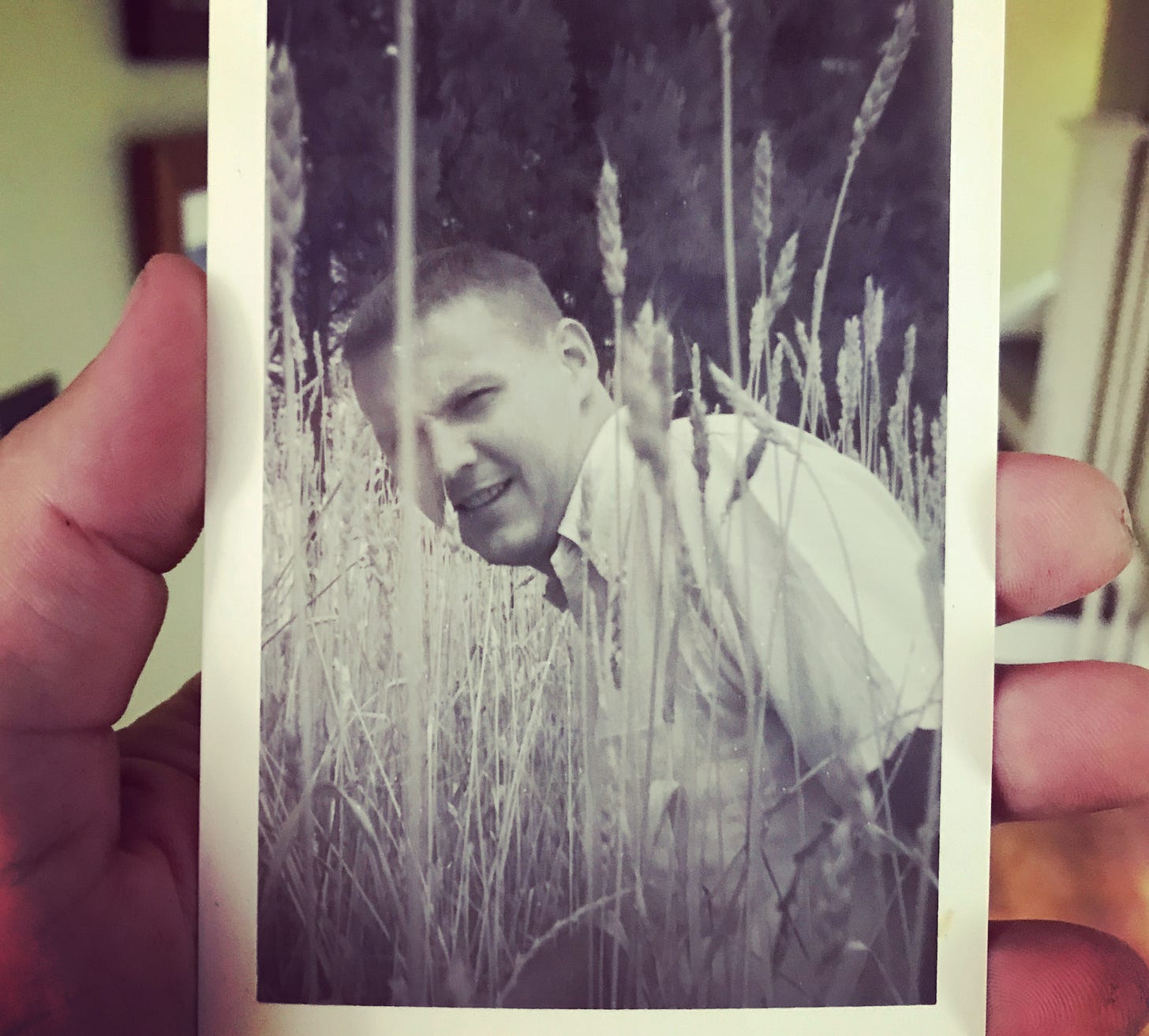

When I’m out in the world, longing for family, I launch a reconnaissance mission to learn more about my namesake. At nineteen, I impetuously drive 340 miles to my paternal grandparents’ home, walking through their bungalow door for the first time in twelve years. On this brief visit, Granddaddy and Grandmother Warren do not talk much of their youngest son, yet in the pale rooms of his youth, I feel closer to him.

When my father’s parents pass at the dawn of the 90s, I use a meager inheritance to buy my first quality acoustic guitar – a Martin – and pay for acting school. I dream big. The odds of realizing my dreams are long, but the more folks die around me, the more carpe diem I become. It becomes increasingly easier to fight against the voice that says, “You’re asking a lot, y’know.”

I track down and converse with Burke’s aging friends. Most respond with notes and brief conversations limited mainly to “he was a great guy.” My Aunt Margaret, married to my father’s brother, strikes up a correspondence, sending photos and sweet letters. Although not my blood, she will respond more than anyone to my desire to know my father. I visit her, my Uncle Tommy, and my cousin Robin in Medfield, Massachusetts. Uncle Tommy, ten years older than Burke, won’t give much information, except to say his little brother was “a health nut,” and that several young women thought they were my dad’s fiancee, when they were in fact not.

Aunt Margaret reads the book Driven to Distraction: Recognizing and Coping with ADHD. It makes her feel seen as never before. She strongly suggests I read it. Via letters, emails, and phone conversations, she shares difficulties of life with my uncle, and two of my cousins. She is certain undiagnosed ADHD explains much of her loved ones’ exasperating, enraging natures, even the strain of alcoholism that runs through the Warren line. She is certain ADHD explains my wayward father, and particularly my mercurial brother, who, following Burke’s death, develops anger issues and drops out of high school. In me, Aunt Margaret astutely recognizes a fellow enabler and pleaser. She wants me to feel seen, too. This as a life-changing kindness.

That said, I do not believe what we now call “attention deficit hyperactivity disorder” accounts for so much. In my family or, for that matter, anywhere.

Perhaps the strangest aspect of my recon mission is when twinkly-eyed, septuagenarian women share salty anecdotes about my pops. That time he answered the door in his underwear. That time he sang “The Wayward Wind” (or was it “Can’t Help Falling in Love”?) over the phone to a girl who was not his girlfriend. Canoodling extramaritally. All stories ring familiar, especially the ones in which charming, casually cruel Burke behaves with no apparent concern for consequences, no conscious realization of how much he has to lose.

Without really knowing my old man, I compulsively choose companions who share some of his traits. Risk-takers. Time-blind addicts. Charismatic liars. Talented tyrants who (supposedly) need taking care of, who repeatedly, even unabashedly, take advantage of me. Eventually I snap and deem some act unforgivable, which helps me abandon the web I helped weave.

With the perspective of time and distance, I realize my culpability in all of the above. My initial, subconscious ignoring of red flags now blazing bright in the rearview. I ruminate, spin damning stories, repeatedly re-enact in my mind. I am a skilled storyteller, and that’s both the good and the bad news.

In the parking lot of Woodstock, NY’s Sunflower Foods in the waning second Obama administration, I initiate a long telephone conversation with Burke’s generous, now seventy-something cousin, very likely the last person to see him alive. Aunt Margaret has put us in touch. He informs me my father could, and often did, eat a whole can of pitted black olives. He says Burke adored my brother and me, talked about us all the time, loved when we visited his and our stepmother’s apartment, visits I recall hazily but fondly. Except that time my brother and I pulled Burke’s Marine sword from a high shelf and I almost impaled my sibling, which naturally freaked our dad out. I’m glad he yelled and swatted out butts, though, because otherwise I don’t think I’d remember it.

Burke’s cousin insisted my father stay with him at the Hilton after they’d gotten shitfaced that April night in 1972. Burke promised he would. But when the cousin awoke hungover the next morning, he realized Burke had bolted in the wee hours. The cousin couldn’t bring himself to be in Atlanta for years afterward. Some PTSD, lacerating guilt, and the grind of shame.

I tell him it’s OK. I understand. By now, I’ve also made a mistake that likely led to the death of a friend driving intoxicated, this time on a motorcycle. It’s easy to forgive my father’s cousin. To forgive myself for inadvertently playing a role in my friend’s death – and to forgive others who really need that from me – I’ll need help.

I will get it from a psychedelic “journey,” and an intuitive, empathetic guide. For a couple of unforgettable autumn days, I’ll forgive everyone.

NEXT WEEK: Psychedelic Sexagenarian Part 3: In which I take my medicine

Such beautiful commentary.

Just beautiful!