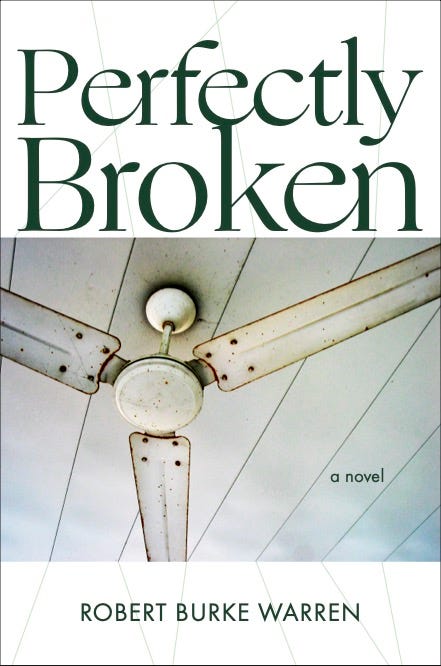

Since it was published in 2016, my debut novel Perfectly Broken has received 4.18-out-of-five stars on Goodreads and 4.4 on amazon. Excellent blurbs here. I’m now serializing it, a chapter every Tuesday, for paid subscribers. All subscribers, paid or not, may read an enticing portion of each post.

Scroll on and see.

If you’re not yet a paid subscriber, you can be one for at as little as 5.00 a month. Think about that. In addition to my serialized, scandalous novel, you’ll get more Premium Content, and of course my deep gratitude. If you wish to buy a copy of Perfectly Broken for the cost of a couple of lattes, I suggest eBay.

Thanks so much to all of you. I look forward to any comments and/or questions. Writing Perfectly Broken altered the course of my life. It brought people pleasure, made some blush, and enraged at least one. I’m proud of it. I hope you enjoy the work.

RBW

PART ONE

JANUARY 2003

Chapter 1: Chicken Bomb

The ache in my thighs reminds me of jumping off speaker cabinets during a show by my former band, Stereoblind. A similar burn troubled my leg muscles back then, in the late eighties and early nineties, when I’d wake up in a strange bed, post-gig, stiff from exertion, ears ringing, the occasional sleeping stranger at my side. All pre-marriage, pre-fatherhood.

This pain is from walking up and down, up and down five flights of stairs all day, removing my family’s possessions from our tenement apartment. I straighten up from the final duct-taped box marked “MIXTAPES—’97,” and step back from the U-Haul trailer to assess our material goods: TV/VCR combo, vintage (and faux vintage) clothes, furniture salvaged from these very East Village street corners, a dozen or so saved LPs (unplayed for years), my wife Beth’s chapbooks and dog-eared spiral-bounds, and my 1962 Ampeg Portaflex B-15 bass amp.

In planning this dreaded day, I’d insisted we forgo professional movers, opting instead to spend hours cramming everything into our ’95 Camry and the trailer. Save a few bucks, assert some male brio, compensate for four years of decidedly non-macho stay-at-home dadhood.

Beth did her part, boxing and bagging up our life, working up a dusty sweat. She’s in better shape than me. In a threadbare, sleeveless Pyramid Club T-shirt, her anterior deltoids still ripple, remnants of a corporate gym membership now months lapsed.

Retired rock star Paul, gone for cigarettes and beer, has kept watch over our four-year-old son, Evan, while Beth and I work. He is Evan’s godfather, although they both prefer the term padrino—Spanish for “little dad.” On his credit cards, Paul’s surname is Fernandez. On liner notes, it’s Fairchild.

Of all our friends and neighbors, only Paul came through for us on Moving Day, in part because he has no job. But, as ever, Padrino entertained Evan, shielding him like a jester protecting a boy king from court anxieties. Around noon, he squatted down to inspect Evan’s Sharpie art on the moving boxes.

“Hey little man,” he said. “What’re you drawing? A flying poop? Fuckin’ A! That’s totally a flying poop, like super poop or something.”

After squeals of laughter, Evan said, “Padrino! It’s a bee!”

Beth and I watched from the doorway. She sob-laughed quietly into my shoulder, pressing tearstains into the faded black of my T-shirt.

A new home awaits us, a furnished rental property courtesy of our old running buddies Trip and Christa Lamont. Their rental, a 1900 farmhouse they call Shulz House, is on a dead-end road three hours north, in rural Mt. Marie, New York.

After 9/11, Trip and Christa headed for the hills, buying a couple pieces of land in the Catskill Mountains, far away from the ashes of the World Trade Center and, they hoped, the memories of eight unsuccessful IVF attempts. They’ve since adopted a two-and-a-half-year-old Chinese girl named Katie, and all are nesting in a Victorian down the street from Shulz House. In recent emails, Trip refers to our upcoming tenancy in the Lamont “fiefdom.” This does not strike deeply-indebted me as particularly funny. But Beth and I are desperate and, sight unseen, we’ve accepted our friends’ kind offer of a home.

We’ve not laid eyes on Trip and Christa in over a year. Their recent glossy Christmas card showed only tiny Katie, standing in a snow trench before a garlanded porch, her wide, expressionless face framed by a pink snowsuit hood. Season’s Greetings from the Lamonts! Trip, Christa, & Katie! The forced gaiety struck Beth and me as eerie.

I’ll be digging snow trenches soon, ugh. I’m hoping global warming will keep this task at bay, as I am pear-shaped where I once was Bowie-thin, and easily winded.

I close the U-Haul doors and slide the shackle into the greasy padlock, hands trembling from waning adrenaline, vision sharpened from pain. The cold ka-thunk is satisfying. I dread re-opening this door to assess our stuff, all of it now connected to loss. For a moment, I fantasize a wave rising from the nearby East River, engulfing the U-Haul, and carrying away our material possessions to the Atlantic forever.

But the only thing I’m actually farewelling is our soon-to-be former home: a red brick 1880 tenement looming in the crisp twilight, vined with cables, Christmas tree lights blinking erratic rhythms on the fire escape.

I drop into the Camry beside Beth, and breathe in my family. A groan escapes my lips.

“Papa?” Evan sniffles in his car seat.

“I’m OK, Evan, just a little sore.”

Click. The glove compartment light spills over Beth’s face. She blinks, the rims of her dark, cried-out eyes glistening. “There’s Advil in here if you want,” she says.

I wave away the pill. Beth shuts the door and gazes forward.

“Where is he?” she asks, meaning Paul. “Why does it always take him three times as long to get anything? We need to go, like now, or traffic’ll be a nightmare. He knows this.”

She stares forward. When Paul had asked if anyone wanted a beer for the road, she’d said yes without hesitation, but I do not remind her of this. Nor do I reiterate how waiting for Paul has always been part of having him in our lives. The guy has always made everyone wait, friends and fans alike.

Paul’s erstwhile band Six Ray Star, for instance: they routinely hit the stage at least two hours past whatever time they were scheduled. It was part of the show, this tardiness, part of the performer-audience contract. Their fans loved talking about it, loved to hate it, loved the heightened anticipation. But it always rankled me, like his blasé attitude rankles me now.

I follow Beth’s sightline, as if my attention will make Paul arrive faster, as if Paul is the F train.

The evening waxes on beyond the grimy windshield. NYU students wolf down slices in the pizzeria, lusty-eyed twosomes ascend stoops, breath commingling in clouds. A couple embraces on the curb next to the Camry’s passenger side headlight. The boy lifts the girl, tries to spin her, loses his balance. Beth, Evan, and I gasp in unison as they tumble against our front fender in a tangle of arms and scarves. They right themselves, turn wide-eyed to us, wave laughing apologies, and flee like the children they are.

“Are they OK?” Evan asks, tears rising in his voice.

“Yeah, they’re OK,” Beth says. “Just . . . careless. It’s OK, Evan, it’s OK.”

Ghostly residue of the young couple lingers in my mind’s eye. Not us, I think. That’s not us anymore.

Something crumbles in my chest. Evan’s not the one who’s going to cry. I am.

Due in part, I think, to Zoloft, Evan has never seen me cry. But our financial troubles have forced me to halve my meds, and here, now, I feel my pharmaceutical buffer diminished. I start the car, crank the heat, and try to summon whatever traces of the drug remain in my chemistry. The Camry fills with distraction, familiar chuffs and rumbles, air warming in the vents, headlights igniting on Paul, crossing in the glow. Perfect timing, as always.

He whacks a pack of Marlboro Lights against his right palm, striding as he did across stages back in the nineties, when Six Ray Star rode Nirvana’s raggedy flannel shirttails to indie stardom while I, who’d quit my own band in a huff, watched from the wings. To his godson’s delight, Paul has festooned his battered biker jacket with Mardi Gras beads dangling from the left epaulet. A plastic bag at his wrist swings like a purse, bursting with the promised beer.

My lips tighten. Paul’s slouchy, hip-first gait suggests a lack of concern for my family’s plight. I am refreshingly annoyed, and dry-eyed.

Beth glares as she lowers the passenger-side window. Before she can speak, Paul produces a Rolling Rock from his bag. He grins, Cheshire-cat-like, baring his missing eyetooth gap as he opens the beer with his keyring and hands it to my wife. One fluid motion. No words pass between them. They scan for cops, nod, and Beth drinks deep.

Paul leans in, greasy blue-black hair falling over his forehead. He taps a rhythm on the window frame and laughs.

“You guys look like the Beverly Hillbillies . . . in reverse.” His hoarse voice floats on a yeasty cloud. He fits a Marlboro Light in the corner of his plum lips. “You know what I mean? In reverse. Instead of moving to the big city from the country, you’re . . .”

“We get it,” I say.

Such an asshole.

“Beer for you, Jed Clampett?” he says.

I jerk my head to the waiting road. “Uhm . . . driving?”

“Whatever,” he says, put-upon. “You’re welcome, handsome.”

I glance in the rearview and check my look to see if he’s being sarcastic or not. The verdict: sarcastic. Thinning dishwater hair plastered to my forehead with drying sweat, grime-smeared face. Lovely. I look every hour of my thirty-nine years, and then some. I glance at Evan’s reflection. My son barely fits in his foul car seat. He shudders with another aftershock sob from a recent crying jag and grips a fistful of his Toy Story pajamas. Like all of us, he’s upset about moving. These filthy sidewalks where he took his first steps are the only world he knows, and his love for the neighborhood is strong. If this had gone down two years ago, he wouldn’t have known the difference, but halfway into his fourth year, he doesn’t miss a trick.

My battered black instrument cases flank him, each stenciled with STEREOBLIND. These instruments—my bass, Blackie, and my acoustic guitar, Luther—are as close as Evan is likely to get to siblings.

He is a mini-me of his mother, my son. Except for gender, and Beth’s distinctive gap in her front teeth, Evan is my wife’s clone. He inherited Beth’s Black Irish coloring—dark eyes, almost-olive skin, generous lips (now chapped), all set in a heart-shaped face with a pointy, elfin chin dappled with tiny dark freckles. Although Beth’s been graying of late, they share the same sable brown, dread-inclined hair. With his modified bowl-cut (courtesy of me) he looks like a little Beatle, circa 1963; a puffy-eyed, upset Beatle.

“You OK, Evan?” I ask.

He nods, looks across the street to the apartment building, raises his hand, and waves.

“Bye, home.”

All eyes turn to 244 East Seventh and travel up to the fifth floor.

Paul stiffens. “Hey Grant,” he points up with his still-unlit cigarette. “You left the lights on.”

“Like we care!” Beth says and sips her beer.

Paul is back in the window. “No, I mean you gotta take the light bulbs. Can’t leave that scumbag anything. Dude knows you’re having hard times, raises your rent! Motherfucker. Gotta take the light bulbs. They’re yours. Gotta do it.”

My wife flashes a bitter smile, and closes her eyes. Hard times indeed. Her employer, Electra magazine—“the voice of the hip career woman”—is recently dissolved, her breadwinner editorship no more. A couple months collecting unemployment, and the new lease arrived, our rent increase too much to bear. Due in part to my lack of an income, we are priced out of our longtime neighborhood.

“You didn’t do the chicken bomb, Grant,” Paul leans further into the car, his face aglow in the panel lights. “So you gotta at least take the light bulbs.”

There’s a rustling in the backseat. “Papa . . . what’s a chicken bomb?”

“Nice going,” Beth says, slapping Paul’s hand.

“It’s nothing, little man,” Paul’s shoulders are in the car now. He cranes his head toward Evan, forcing Beth to duck. She throws me a glance, a familiar: Can you believe this guy? But for a moment, she shines.

“Alrighty!” Beth says, sinking back into her mood. “Thanks so much for the help, Paul, and the bevvies. We should go, Grant.”

Paul opens his palm next to Beth’s face. “Gimmie the keys, boss lady,” he says, grubby digits wiggling in fingerless gloves. “I’ll get the light bulbs.”

A tug at the corner of my wife’s mouth may or may not be a smile.

“Wait,” I say. “I’ll do it.”

Beth hands over the keys and focuses on me for the first time today, everything dilating, lips parting.

We’re kissing goodbye? Like fourteen years ago, when five minutes was forever?

I’m tumbling toward contact, looking forward to the taste and texture of beer on my wife’s lips, when a renegade hair dances across her face. She flinches, and jerks back. Her eyes flick to Evan, our unwitting chaperone, then back to me.

“Go,” she says, retrieving a case of mixtapes from the floorboards and buzzing up the window on Paul’s goofy smile.

Paul and I cross the street in the frigid East River wind. He huddles behind me, the plastic bag crinkling. A shadow moves.

“Hey.”

We look to the vacant storefront next door to our stoop. Leaning against the pulled-down gate is Beth’s junkie little brother Billy, crumpled into a dingy hoodie, shaking with drug hunger chills, eyes popping.

“You guys still need a hand?” he says, his voice raw, faux-casual. He sniffs and rubs his nose, smiling, all overlong teeth and graying gums. “What’s up, Paul.”

“Hey fly guy, good to see ya,” Paul says.

“Thought you were coming at noon,” I say, disappointed to see my brother-in-law, yet also validated. I knew he’d been lying about being clean. I look back to the car, hoping Beth and Evan don’t see this hepatitis C-decimated wraith.

I’d been relieved he’d stood us up. Against my better judgement, I’d suspended my moratorium on contact between Billy and Evan. Part of our current crisis is due to Billy’s recent failed rehab stint, which cost us about twenty-five grand. He’d checked out early, but they refunded us not a penny. That was the final straw for me. But Beth, ever forgiving of her little brother, insisted Billy should be able to see us all off, especially as he claimed to be one month clean, all on his own, and we certainly wouldn’t be seeing much of him in our new digs.

I’d caved. He’d pitch in, she said. He’d been lifting weights, couldn’t wait to show us how healthy he’d gotten. But, as ever: all lies. Part of me wants to drag him to the car to prove I was right, a rising little genie of spite in my gut, ever more familiar these days.

“I got hung up,” Billy says. “You wouldn’t believe what went down at this place I’m staying at over on Rivington . . . this guy’s potbellied pig ate some rotted meat and . . .”

“No time for this, Billy,” I say.

“What?” Billy says as if I am out of my mind, his usual MO. “What’s your problem?”

“Potbellied pig?” Paul laughs. “That is rich. Imaginative.”

“No bullshit, man! None!”

“OK,” Paul says. “OK. I totally believe you.”

“That pig is at the Animal Medical Center right now,” Billy says. “Call and see. Call. She’s fucked up, that pig. My friend can’t pay. They’re gonna put the pig down!”

Paul digs in his pocket. “What do you need, Billy boy?” He produces a crumpled twenty.

“I don’t need shit,” Billy says. “My friend . . .”

“No, Paul,” I say, pressing the twenty back. “It’s just going up his arm.”

“What?” Billy says. “I’m a month clean, Grant, you fucker. No thanks to you. I just got hung up today. I got hung up. I know you don’t give a shit . . .”

Billy snatches the twenty and glances over at the Camry, then back at us.

“No skin off your nose, right Pablo?”

Paul shrugs.

“She OK?” Billy says. “My sister?”

“She’s great,” Paul says. “Evan, too. They’re fine. You can catch up with ’em later, right?”

Billy is moving away, energized by the money in his hand. “Yeah, yeah, you know it. I’ll be in touch. Tell her I had to bolt, it was an emergency. Tell her I love her, bon voyage, you know.”

“We’ll do that,” Paul says.

Billy races off.

Before I can open my mouth, Paul says, “If she’d seen him like that, she’d have lost her shit, right? I just stopped him from needing to steal something to sell. Admit it: you’re relieved, right?”

I have to admit I am.

In the stairwell, Paul shifts into raconteur mode, talking half to me, half to an unseen audience, marking time, as always, by what Six Ray Star was doing in bygone days. I’m too tired to remind him I’ve heard this tale, but that wouldn’t stop him anyway.

“The chicken bomb at my Second Street digs was the best,” he says. “We were on Matador, before we got on Warner Brothers, and I got evicted for some bullshit, and Billy was still working at Leshko’s and freakazoid Billy says, ‘Chicken bomb! Chicken bomb! Let’s do a chicken bomb!’ Which we did, the best ever. Billy gets this big gallon pickle jar from the Leshko’s kitchen and puts a chicken carcass in it, stuffs anchovies and some other shit in there, pours in some milk, screws it shut, duct-tapes it, and on the day I move my shit out, he hides it in a hole in the wall behind the radiator. It’s getting on towards winter, and the radiators come on, like, super hot, and that chicken starts to putrefy and the jar fills with gas and ’round about Christmas—right when we get back from a tour with White Zombie—the fucker explodes! The shithole reeked for months! Ho, ho, muthafuckin’ ho!”

I turn the Medeco and push open the apartment door as Paul laughs. The thought of chicken bomb revenge is tantalizing. But Beth and I agreed it would be hard on the neighbors. So when Paul offered to facilitate the prank, we’d declined.

Paul never thinks like that. Although forty-one and approaching jowliness where he once was chiseled, he still functions like a kid, with no thoughts of consequences. This “childlike” quality of selfishness, however, combined with a somewhat secret, shrewd business sense, has made him a millionaire in torn jeans and rundown boots.

Six Ray Star did well, mostly from touring, but Paul didn’t really score until after they disbanded in ’98, and music supervisors came calling. He’d held onto the rights to his songs, so now all licensing fees from commercials, soundtracks, and video games go straight to him. And music supervisors cannot get enough of Paul Fairchild. His most notable coup is a deathless international Nike commercial. If he and his wife had offspring, which they don’t (and won’t, they say), those kids would never need to work. If anyone’s the Jed Clampett of rock and roll, it’s Paul.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Robert Burke Warren, Showfolk to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.