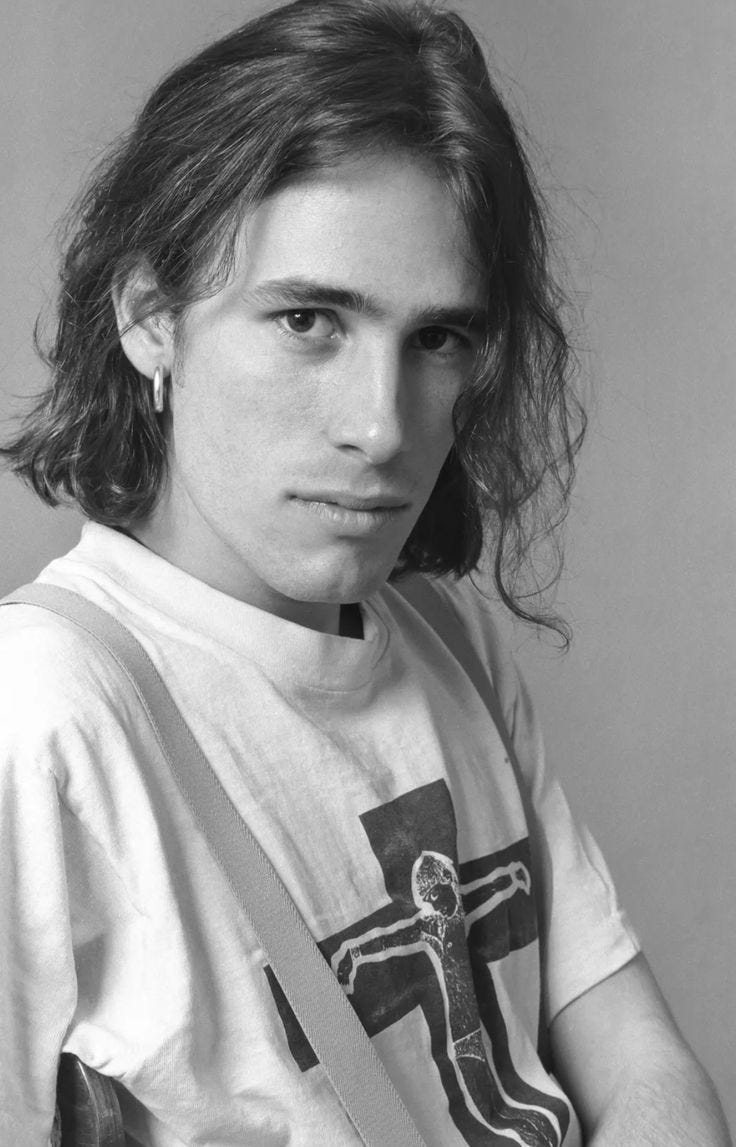

At first glance, Jeff Buckley seemed just another grubby East Village twentysomething boy-man. Jeans loose on slim hips, haphazard hair, ragged tank top.

The eyes, though. When he approached me in the dim light of Sin-é, I met a magnetic, haunted gaze.

“Good stuff, man,” he said of my songs. We shook hands, soul brother-style. For a slight guy, his grip was solid. His smile drew my focus to a generous mouth, full lips. Inflamed from use, I reckoned.

“Thanks,” I said. So this is him. Let’s see what all the fuss is about.

“I’m Jeff.”

“Robert. Looking forward to your set.”

He nodded. With an ease I recognized, he unpacked a blonde Fender Telecaster. Clearly, like me, he’d pulled an instrument from a case thousands of times.

Jeff had arrived with a handful of companions toward the end of my band’s performance. About twenty people still lingered. This was a good crowd for Sin-é, especially on a weeknight. In this tiny sliver of time, my draw was better than Jeff Buckley’s. Not bragging, just reporting.

Outside, on St. Mark’s Place, springtime dusk descended. The scent of fresh leaves in nearby Tompkins Square Park. I was twenty-seven. Jeff was twenty-five.

In those days, I purveyed tuneful rock, my icons Paul Westerberg, Chrissie Hynde, REM. My fitful early work exists now only in my mind and on poorly-labeled cassettes hoarded in the attic. Documented therein, one can still hear me shredding my voice, singing too high, trying too hard.

At twenty-seven, I’d already been a musician for half my life, mostly a bass player. I’d toured the world in the Fleshtones, played on an unreleased album recorded at Electric Lady Studios by Island artists Pleasurehead, and endured the rock star shenanigans of ex-Jesus & Mary Chain John Moore (Polygram’s “next Billy Idol”). Now, I nursed rock n’ roll singer-songwriter ambitions. With a handful of earnest tunes, some fellow showfolk, and a six-string, I’d begun searching for my voice, my groove, in front of people.

I was about to witness Jeff Buckley do the same. Unlike me, he sauntered into the spotlight (although there was no actual spotlight at Sin-é) without the safety net of a band. His voice would be unlike any I’d heard – raw, overwhelming. As if that voice somehow knew its days were numbered in the vessel of Jeff.

Thirty-odd years later, this will be the gig story that best captures the colonized attention of my young guitar and bass students.

If we wanted to – and sometimes we did want to – my wife Holly or I could throw a rock from our 113 St. Mark’s Place bedroom window and easily hit Sin-é. Proprietors Shane Doyle, and a teenaged Karl Geary, both Dublin charmers, had launched their little storefront enterprise at 122 St. Mark’s in 1989. (Sin-é – pronounced shih-NAY – is Irish for “that’s it.”) Despite having no license, Shane somehow got away with selling lots of Rolling Rock. The microphones stank of beer and who knows what else, there was no stage, and remuneration was pass-the-hat. Nevertheless, Shane knew folks like Bob Geldof and Hothouse Flowers. Thanks to his savvy, and fierce devotion to live music, Shane’s joint became a chill refuge for rock stars – especially Irish rock stars – and a daytime hang for locals young and old.

Karl often opened Sin-é in the early afternoon. The rattle of the gates rolling up frequently jolted me from slumber that had begun at dawn. As the day waned, Sin-é patrons read, wrote, and enjoyed low-rent, unplugged lives amid the scent of cigarettes, scones, and espresso.

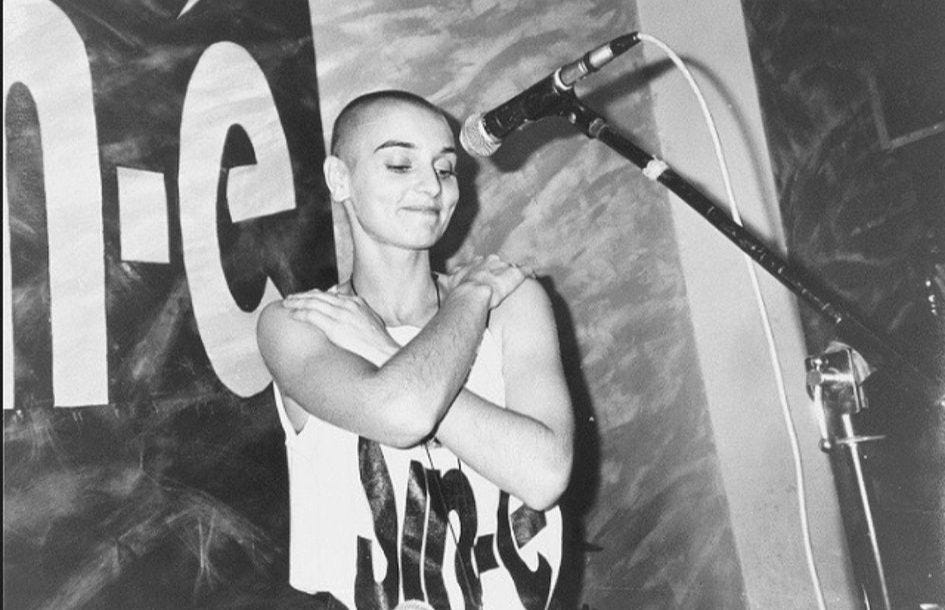

On the stoop outside, I’d met elfin, riveting Sinead O’Connor, who copped weed at the “African arts store” nearby. While burning holes into my soul with her saucer eyes, she’d kindly accepted my umpteenth demo tape, shoving it in the breast pocket of her biker jacket, after which I’d fled. One fraught night, Shane drafted me into service as soundman for an impromptu Marianne Faithfull set. I struggled with the sticky mixing board, shriveling under Madame Faithfull’s diva glare. Another evening, I walked in to find our irritated neighbor Allen Ginsberg sitting with his harmonium in the middle of the crowded room, trying to sing while a drunken guy repeatedly yelled, “HOWL! HOWL! HOWWWWLLL!”

By early ‘92, Shane was booking me frequently. He appreciated my nascent promo skills. When he invited me to open for this guy Jeff Buckley, son of 60s “psychedelic folk visionary” and heroin casualty Tim Buckley, he said, “This kid is quite good. And he’s got label interest.”

All I knew of Jeff’s dad was the man had possessed a multi-octave voice, and, like my own father, elder Buckley had died young, beautiful, and high. A stranger to his son. The only Tim Buckley material I recognized was his “Song To the Siren,” specifically the 1983 hit cover by This Mortal Coil. It graced the first mixtape a woman made for me.

As I spread the word about my upcoming gig, I learned Jeff enjoyed what we musicians jealously call “the golden buzz.” In pre-internet days, this was a kind of obsessive, gossipy word of mouth. A strikingly powerful, motivating brand of storytelling that feeds on itself, creating a coveted aura. When this buzz is bestowed on a peer, one must beware of one’s unpretty envy. I managed this reasonably well, at least outwardly. Surely my time would come.

Several in-the-know folks mentioned the Hal Willner-produced Greetings From Tim Buckley tribute at St. Ann’s Church in Brooklyn the previous year. This is where the golden buzz was sparked. Jeff had come out of nowhere – Los Angeles, actually – and stolen the show. Back west, he’d played guitar for years, even semi-pro, but the St. Ann’s gig, remarkably, had been his singing debut. With accompaniment from ex-Captain Beefheart guitarist Gary Lucas, Jeff slayed four of his father’s operatic tunes. Jaws hit the floor. Clearly, this kid was anointed. To hear Lucas tell it, young Buckley was as surprised as anyone when he uncorked that voice. Willner would later say when Jeff did the tribute, he “stepped into another life.”

Following the St. Ann’s gig, Jeff moved to the East Village. My ‘hood. Gary Lucas became an indispensable mentor, foil, and friend. They worked up some sophisticated, soon-to-be-seminal originals like “Grace” and “Mojo Pin,” performing as a duo at the Knitting Factory and Brooklyn’s Roulette Club.

At unassuming Sin-é, Jeff would finally fly solo, albeit in an unpredictable way. When he eventually traded anonymity for fame, he would forlornly say of these “cafe days”: “I [had] that precious and irreplaceable luxury of failure, of risk, of surrender.”

Prior to our shared bill, I think Jeff had only played Sin-é a couple of times, to little fanfare. No advertising or flyers. Just people sharing eminently repeatable stories about something unusual happening in the cafe with the oft-mispronounced name.

Did the smattering of Sin-é patrons immediately swoon over Jeff Buckley in Spring of ‘92? They did not. Some, like me, would be as irritated as they were mesmerized.

As I sat with Holly and some friends, unfolding crumpled bills from the tip bucket, Jeff hustled over.

“Hey man,” he said, his hand sweetly heavy on my shoulder. “You got a capo? I forgot mine. I can’t believe it. I always forget shit.”

“I do.”

“Could I borrow it? Please?”

It wasn’t really a question. I said yes, of course, and grabbed it from my case. Jeff held the capo in his hands like a string of prayer beads, bowed, thanked me, and strapped on that Tele.

When he launched into a raucous rendition of the Van Morrison waltz “The Way Young Lovers Do,” my pulse spiked. His propulsive rhythm, and that unhinged voice, pushed the meager sound system into the red. Such soul-stirring, borderline-disturbing vocal intimacy I would rarely experience going forward. The swoops into the stratosphere, the growling and keening. Sexual, spiritual. This was Freddie Mercury territory, all through a cheap microphone and distorted speakers in a tiny room.

A smattering of applause. Young women shifting in their seats. What the fuck just happened? A couple more songs I didn’t recognize, probably early versions of “Grace” and “Mojo Pin,” both of which showcased Jeff’s gifts in more measured way than the Van tune. But still: those pipes! And his guitar work. Truly, it was like witnessing both Robert Plant and Jimmy Page in their prime. Actually hard to process in the moment. Holly and I exchanged glances. Can you believe this guy?

And then… the goofiness.

Once it became clear he’d captivated us, Jeff willfully broke the spell. He struck up a chat with a friend in the audience. Seemingly for the friend’s benefit, he jokily – albeit expertly – picked out the intro to “Stairway to Heaven,” stopping just shy of the first line of the first verse, which both disappointed and relieved me.

This was his routine, apparently. Slay, then lower expectations. At the time, I despaired he was squandering his lottery winnings. Like: Damn, if I had that talent, I would not be fucking around like this.

I was wrong, though. I understand now he was purposefully making himself vulnerable. The opposite of what addicts do. To my knowledge, he liked his weed and wine, but he wasn’t dependent, like his dad. His mother, Mary Guibert, has said he was very conscious of his DNA legacy, and determined to tread accordingly. Now I think: rather than numb himself with a false sense of being bulletproof, he went the other way. While mastering his gifts before a live, and, crucially, non-paying audience, he would grant them ever more power to reject him. If and when they did, he would take it straight, recover, return, all onstage. Quite a bit of performer derring-do there. I imagine him thinking, “Can I make myself so good, folks will put up with my obnoxiousness, even welcome it?” Answer: yes.

People ask if he played “Hallelujah.” I have no recollection of that. If so, he would have employed my capo, on the sixth fret. Perhaps he did, but it was so astonishing, my steel trap brain went offline for a few minutes. That is possible. I do recall a punky “Kick Out the Jams” (MC5) more jokey jamming, more chatting, then Jeff killing the Edith Piaf chestnut (written by Margueritte Monnot) “Je N'en Connais Pas La Fin (I Don’t Know the End).” As he transitioned effortlessly from French to English, all while making that Tele sound like a calliope, I’m like: Give me a fucking break.

Eventually, the capo was back in my hands, Jeff was thanking me again, bidding me goodbye. The small crowd spilled onto the cooling St. Mark’s sidewalk. My wife and I crossed the street to our home, bound for our unmade bed, certain to be further unmade quite soon. For our time and attention (and, I guess, the capo loan), Jeff had given us another Sin-é memory to share in decades to come, though I’m sure that’s not what we were thinking. Not exactly.

Within a couple months, folks would make a lot of hay over the amount of beautiful young women attendees at Jeff’s Sin-é gigs. A fellow envious musician will say, “Not a dry seat in the house.” Those women will gladly cram themselves next to record company gate-keepers, dream-makers. (All dudes.) As autumn takes hold, limos will line St. Mark’s, looking weirdly funereal from our fire escape.

Come October, Jeff will sign a $1 million dollar deal with Columbia, home of Springsteen and Dylan, and his cafe days are done. He has five more precious years in this realm, a whirlwind of bona fide rock stardom, restlessness, and creative activity. When he dies at age thirty in a freak drowning in Memphis on May 29th, 1997, Holly and I are eight months away from becoming parents to a beautiful son.

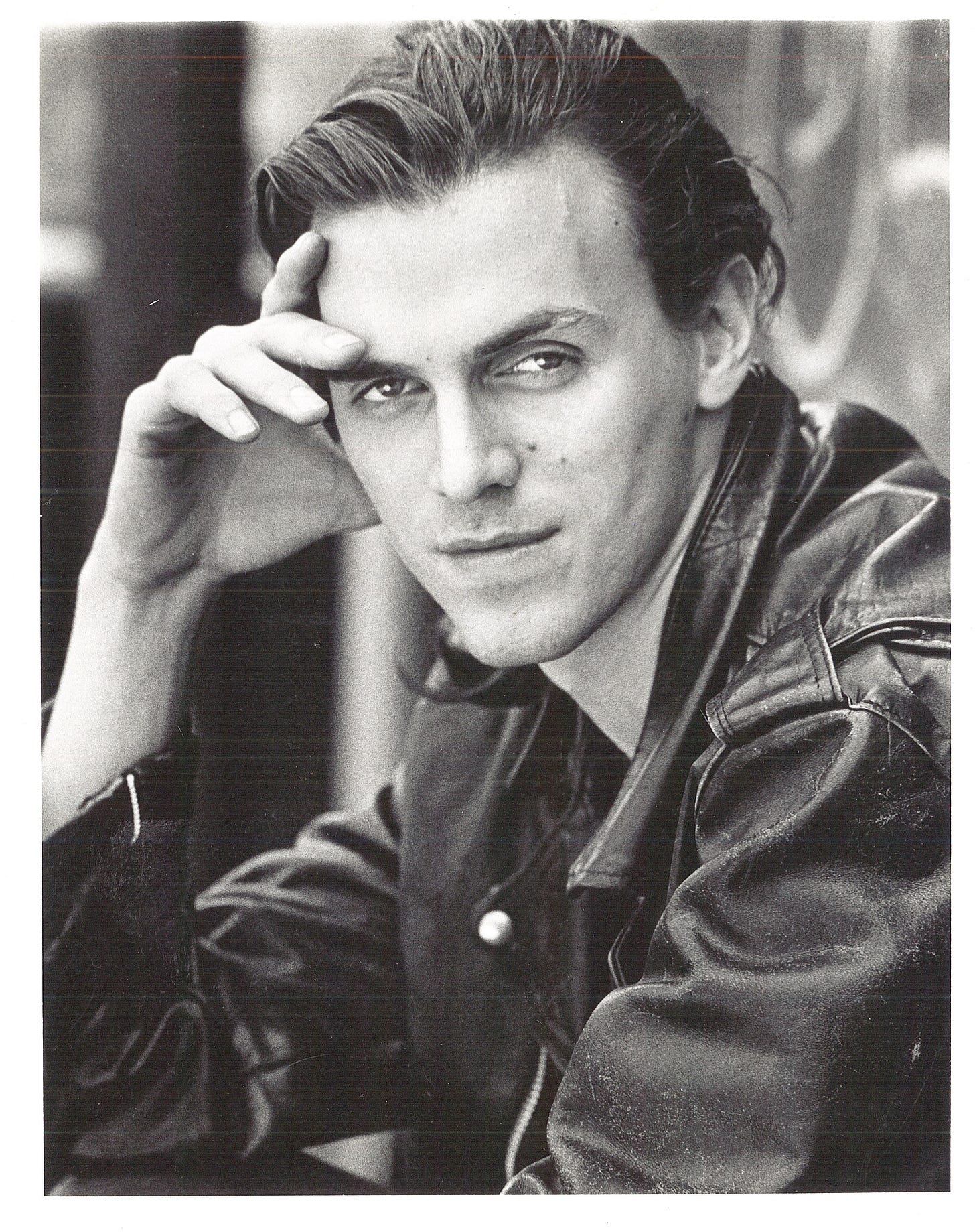

I saw Jeff Buckley in the flesh one more time after our gig. He was crossing St. Mark’s alone in a nice black coat, heading in the direction of Sin-é, frowning, those lips purplish against the white of his face, the dark of his eyes. In the russet light bouncing off the tenements, he was sans guitar. Smaller. A man with a dream come true in his pocket. Part of me wanted to approach, to congratulate, to remind him I helped him that night. That would’ve make me too vulnerable, though, so I just let him go.

…For Shane. Go raibh suaimhneas síoraí air, and thank you.

Sin-e wow! That's the place. You have to see my friend Amy Berg's documentary when it comes out. It's called It's Never Over, Jeff Buckley. all about that time (and with blessing from his mom who gave it to no one else). Loved this, Rob. You captured that time.

I saw Tim Buckly perform in the mid-60s. He was totally amazing. He had one album out at the time, and I bought it.