When I look at a v-shaped scar on the base of my right thumb, or when rain makes my right hand and left wrist ache, I recall my Season of Broken Bones.

We’re talking spring of 1977, when I fractured two bones in my right hand, and, a couple weeks later, two bones in my left wrist. The fractures I managed on my own. The thumb laceration, however, was inflicted by a medical professional.

PART 1: BOXER’S FRACTURE

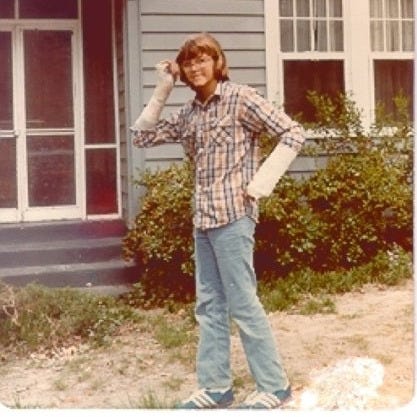

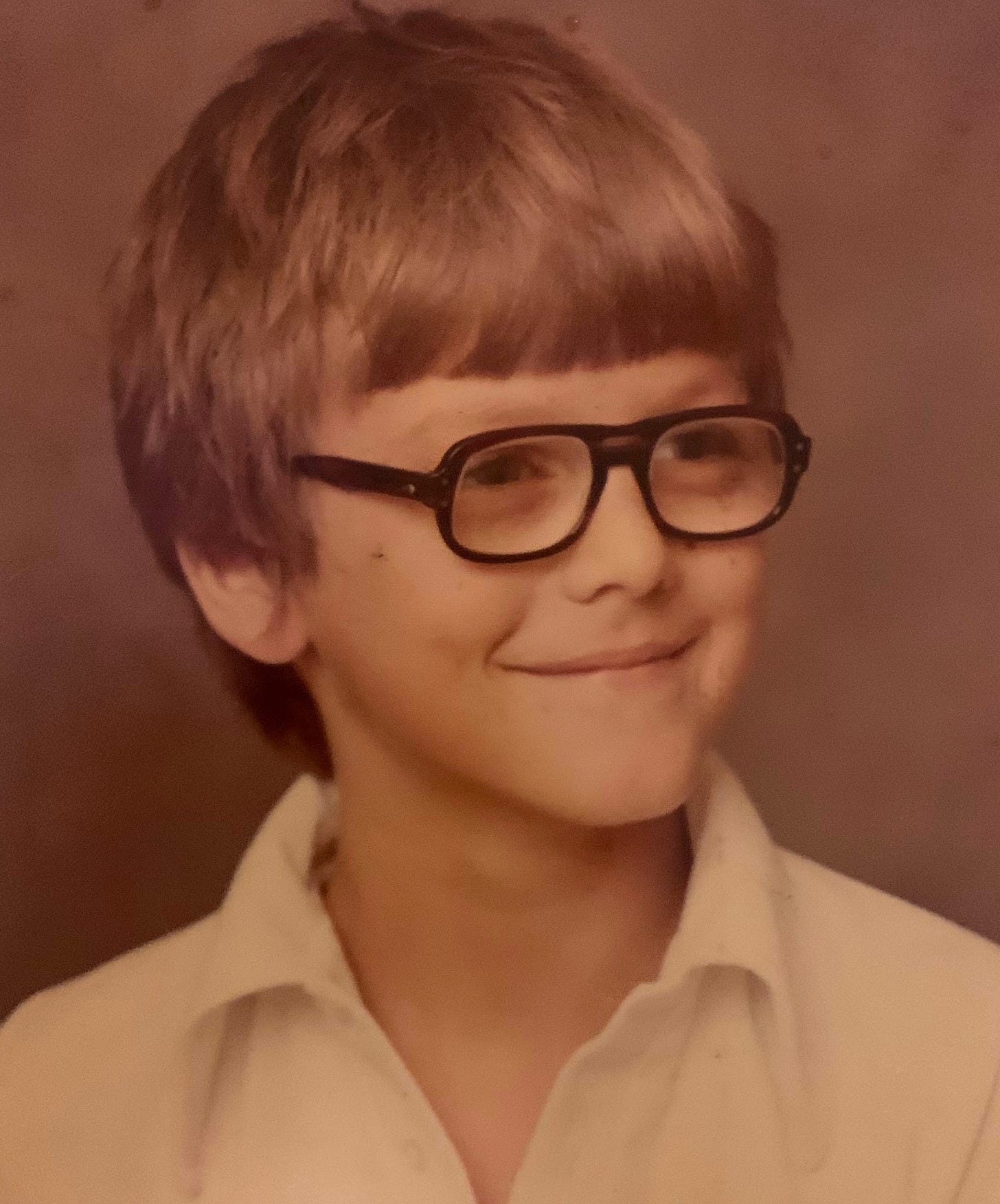

In spring of ‘77, I’m a twelve-year-old Kiss fan, an avid radio listener, a bookworm. Not yet a musician, partly because I keep injuring myself.

Sixth grade at Christ the King elementary is winding down. Because my homework is incomplete, Miss Salome announces, “Robert didn’t finish the assignment, so he will not be joining us at the Friday party.” So while everyone eats cookies, guzzles Coke, and flirts, I’ll be exiled to a corner, dunce style.

In years to come, I will craft a designated-driver persona, but in ‘77, I’m a nutty adolescent. An unpredictable rage smolders in me, plus I’m girl-crazy, easily unhinged by the classroom potpourri of Love’s Baby Soft and Clairol Herbal Essence.

Miss Salome’s shaming spurs in me some epic overreacting, one of the Top 10 dumbest things I’ve ever done.

Word to the wise: if you’re going to punch something, like, say, a slab of metal, connect with the knuckles of your index and middle fingers. The bones extending from there to your wrist are significantly stronger than the ones extending from the ring and pinky knuckles.

Of course I know none of this when I stalk into the hall and slam the weak side of my right fist into a locker, snapping those two bones (3rd and 4th metacarpals). My ring and pinky knuckles disappear. Students turn to see the source of the BOOM.

Pain radiates up my arm. Somehow I know what I’ve done, but I’m weirdly calm. I hold my hand before Miss Salome’s pinched face and say, “I think I broke my hand. See? I can’t make a fist.”

Miss Salome rolls her eyes and sends me to the office. I call my grandmother, Gammie. 404-233-1006. Within an hour, I’m at Atlanta’s Piedmont Hospital, sitting across from burly, fifty-nine-year-old Dr. Pierce Allgood .

“What’choo done to yourself, boy?” twangs Dr. Allgood. He squeezes my shoulder, shakes me softly, meets my bespectacled face with smiling eyes. He knows exactly what I’ve done. I will learn my affable orthopedist grew up on a Marietta, Ga. dairy farm, where he made truck deliveries when he was twelve. My age. I feel no judgement from him.

Dr. Allgood numbs my injury with a shot of lidocaine. He briefly focuses on my x-rays, explains a “boxer’s fracture,” and tells me how he’ll fix my hand, which he remarks is big and beautiful.

“You gonna be tall, son,” he murmurs.

Little do either of us know how important that hand will be. Actually, perhaps Dr. Allgood does know. But we’re not discussing the future. He is confidently piloting us through our mutual now.

He takes my hand in both of his. With elegant fingers, her casually manipulates the broken bones back into place. Like he’s snapping Legos together. Even with the lidocaine, it still hurts. I grit my teeth, squirm a little.

“Almost done, partner,” he says quietly. “Be still, now. You’re doin’ great.” It takes maybe a minute.

This is one of the best doctor-patient interactions I’ll ever experience. Satisfied he’s set my bones as well as possible, Dr. Allgood wraps my forearm and hand snugly in gauze, and warm, wet plaster, immobilizing everything for optimal healing.

Eventually, I’ll be amazed at my bones knitting themselves back together perfectly, aided by the touch of an expert healer. At the time, however, I’m mostly wondering if a certain girl will still let me touch her butt (over her skirt) with a cast on. (She will.)

PART 2: BOTH-BONE FOREARM FRACTURE

I return to sixth grade with an attention-grabbing elbow cast, but my Season of Broken Bones has just begun.

A couple weeks after the locker-punching, Boy Scout Troop 165, featuring First Class Scout RBW, goes camping at Cumberland Caverns in McMinnville, Tennessee, about five hours from Atlanta. On the agenda: qualifying for the physical fitness skill award. My elbow cast does not slow me down, and no one advises caution. (It’s the 70s.) I’ve been bequeathed a natural athleticism from my deceased dad, and while not competitive, I’m fast, and I can jump high and far.

On my final broad jump, I run at top speed and leap with extra force. Perhaps the cast on my right arm throws me off-balance. All 130 pounds of me, moving with great velocity, lands on my outstretched left arm, snapping both bones in my wrist, and displacing them. I spring from the ground howling, my arm now featuring an extra elbow.

“Oh my God! I broke my other arm!” I wail this multiple times. The jagged bones come very close to breaking the skin, but thankfully do not.

A Tenderfoot asks, “Is it sprained or broken?”

“Oh it’s broke,” an adult says darkly.

Scoutmaster transports me to a rural clinic staffed by a South Asian doctor and two older white country women. An odd sight indeed for 1977 backwoods Tennessee. The doctor cannot, will not try to set the break. Scoutmaster must drive me the five hours back to Atlanta, my mangled arm in a splint, an ice pack melting in my lap. The mountain doctor has given me a mystery pill, but says if I take it, they won’t be able to set my arm when we get to Atlanta. So I never take it.

I stare out the window at rural Tennessee and northwest Georgia passing by. I’m desperate for distraction. Agony, however, blocks out everything. The information this journey provides me – about pain, endurance, time perception, maybe even God – will inform the rest of my life.

I moan and weep intermittently. Scoutmaster, jaw set, probably feeling guilty, says little. I wonder why I’m so unlucky. I keep quietly imploring why. I’m not a religious kid, but I am fascinated by Bible stories of intervention in times of crisis: God to Abraham, God via burning bush to Moses, Gabriel to Mary, Jesus to Saul on the Road to Damascus.

Isn’t this my hour of need? When the voice of God comes? The angelic presence in the room? The miracle? Not today.

But lo, dear reader, verily my savior awaits: A man in a white coat, a former milk-delivery boy with actual lifesaving, pain-killing skill, and drugs bestowed by science.

Dusk is falling when we arrive at Piedmont Hospital. We soon discover I could have taken the mystery pill (probably Percocet) from the Tennessee doc, as it’s too late in the evening for Dr. Allgood and his cohort to set my arm. For this one, he’ll need a team.

Finally, someone doses me. The pain recedes. In a flash, I understand drugs. I somehow sort-of sleep alone in a dark, air-conditioned hospital room, my fractured left arm throbbing, wrapped in a splint, laying across my chest.

I awake in the wee hours to the kid in the next room screaming “Oh my leg! Oh my leg! Oh my leg!” I’d met him when I was admitted. From his wheelchair, he’d detailed a failed attempt to jump five trashcans on his BMX bike. I’m pretty sure his injury is worse than mine.

When I’m roused at dawn, jovial, faux-exasperated Dr. Allgood is grinning over my bed.

“Good Lord, Robert, you must love it here.”

I shake my head, No.

Dr. Allgood’s strong fingers are in my dirty hair. “We’re gonne get you fixed up, partner,” he says.

My last memory before bone-setting is of being wheeled into the OR, masked Dr. Allgood waving. The anesthesiologist puts me under. When I’m out, my orthopedist exerts quite a lot of torque on my broken arm, pulling and grunting. There had been talk of maybe inserting metal plates and screws in my wrist, but Dr. Allgood opts not to. This is the hard way, manipulating bones through layers of skin, fat, tendons, muscles, vessels; realigning the shards like puzzle pieces he cannot see.

I awake with warm plaster encasing my left arm up to my shoulder, and the big, satisfied voice of Dr. Allgood: “No swimming for two months, now. Try to stay out of trouble, y’hear?”

Leaving the hospital, I’m not thinking of the remarkable medical science I’ve experienced, or of Dr. Allgood’s grace and skill. I’m mostly wondering about that girl who permits my curious hands to touch her, and who touches me in return. Will she remain permissive and curious now that both my arms are in in plaster? The answer on both counts is yes, she will. Bless her heart, wherever she is.

PART 3: LACERATION

But what of the v-shaped scar?

The day starts out good. Six weeks after the locker-punching, four weeks after the Tennessee mishap, x-rays indicate my boxer’s fracture has healed well. “Green bone” is growing around the breaks, my body repairing itself.

My left radius and ulna, however, have a ways to go. Nevertheless, it’s time to free my right hand and wrist.

Dr. Allgood, Gammie, and I watch Nurse Hollis brandish a small, whizzing, circular blade, with which she saws off the filthy, graffiti’ed elbow cast on my right forearm and hand. Then, with a pair of huge, gleaming scissors, she begins breezily cutting through the funkified gauze that had protected my skin.

As Nurse Hollis chats away, birdlike, I experience a moment of precognition: she’s going to cut me. I say nothing, which is a mistake, a lesson.

Reading my mind, and perhaps also seeing the future, Gammie says, “Be careful you don’t cut him.”

Nurse Hollis is almost finished. She says, “Oh I’ve never cut–” and promptly slices deep into the meat of my thumb. I convulse and bleat at the shock of pain. It takes a few seconds for the deep red blood to flow. Tears well up, but I do not cry.

What now? What to do? Everybody holds it together. Distraught Nurse Hollis profusely apologizes. I think Gammie may strike her, but she doesn’t. Dr. Allgood is quietly livid. There’s talk of stitching the wound, but the choice is made to tape it and send me on my way. Which is why, forty-eight years later, despite increasing wrinkles, a visible scar remains.

Everybody agrees the sooner I’m back in the distracting Georgia sunshine, the better. Fair enough. As poor Nurse Hollis ministers to my wound, twelve-year-old me fixates on getting the hell out of there. My right hand may be gashed, my left arm still in a full cast, but nevertheless I’ve got work – and play – to do.

Like my bones, the nasty thumb laceration will heal well. A few weeks later, I’ll be totally cast-free, and I won’t skip a beat. I’ll ride my bike solo to a sold-out screening of a new movie called Star Wars. It will change my life. Later, with my best friend, Todd, I’ll experience my first arena concert – Kiss at the Omni, the Love Gun Tour. Google tells me it was December 30th, 1977.

Within five years, I’ll be using my repaired appendages a lot. Todd and I will be musicians, playing on a New York stage with RuPaul.

PART 4: RETROACTIVE GRATITUDE

As I age, I encounter ever more people whose physical pain humbles me, whose stories make my Season of Broken Bones appear quaint. Women who’ve borne children will say, “Nice story.” Folks with chronic pain will say, “So your pain eventually went away? Nice story.” I hear you.

Starting in my thirties, humidity will make my right hand and left wrist ache. It’s OK. I hesitate to even say ow. In the same way grief connects us to what we’ve lost, the shadowy hurt in my healed bones returns me to those warm days when I was on the precipice of a new phase of my life, when the breaking of bones now seems like a chrysalis cracking. Decades on, my frayed nerves evoke retroactive gratitude for my resilient body, and especially for a heroic, life-changing orthopedist named Dr. Pierce Allgood, for whom it was all in a day’s work.

Dr. Pierce Allgood obituary HERE.

JUNE SALE ON PAID SUBSCRIPTIONS! $5 A MONTH OR $45 A YEAR

Ouch, glad that hand healed!

The school photo of you is precious